Voliere

Each year, Elisabeth Schlumpf cares for more than 2,000 birds from all around the world.

As well as saving exotic wild birds from extinction, the Voliere serves as a sanctuary for sparrows and other commonplace bird varieties. During the busy season, managing director Elisabeth Schlumpf often spends 12 hours working at a time.

Birds squawk and chirp. A single door separates Elisabeth Schlumpf’s office from the Voliere aviary and its rescue centre. A few newspaper clippings are pinned to the noticeboard, with articles on Voliere Zurich and the global bird population, and even one about a channel-billed toucan that received a partial prosthetic beak. A stuffed tanager sits on the windowsill; an empty cage rests on the floor. An old PC whirs. The telephone is rarely quiet for long. ‘I’m sorry, it’s the busy season,’ explains Elisabeth.

Elisabeth runs the Voliere. It’s certainly no ordinary job: she spends her time caring for up to 2,000 wild birds and around 50 to 70 pet birds that the Voliere takes in each year. When the aviary is closed, people sometimes deposit the birds via one of two bird flaps, which were installed in 1957. ‘Well before the baby box was set up at the hospital in Einsiedeln,’ says Elisabeth with a laugh. Many birds are also brought to the aviary in person.

When the aviary is closed, people sometimes deposit the birds via one of two bird flaps, which were installed in 1957.

At the moment, there is a young man in the office, cradling a nest in his hands. Sitting in the nest are three chicks measuring half an index finger in length. ‘Those are common redstarts. They won’t be more than two days old,’ says Elisabeth. She shields the tiny birds with a protective hand while she speaks to the man. He says that he moved the nest when he had to carry out some construction work, but found the animals on the ground a short time later. He finally decided to gather them up and take them to the Voliere. Elisabeth explains to the man that moving a nest rarely works – and that he shouldn’t have disturbed the animals while they were hatching and being nurtured.

Elisabeth and her colleagues are currently nursing sixty small birds back to health. Around half of them will make it. ‘Many animals are severely injured when they are brought to us,’ explains Elisabeth. Around one in three have been attacked by a cat. Chicks generally fall out of their nests from a height of several metres. If they were thrown out by their parents, there would have been a reason for it. ‘Birds can sense when something isn’t right with their offspring, and will not raise it. They can’t afford to waste their energy,’ explains Elisabeth.

Elisabeth and her colleagues are currently nursing sixty small birds back to health. Around half of them will make it.

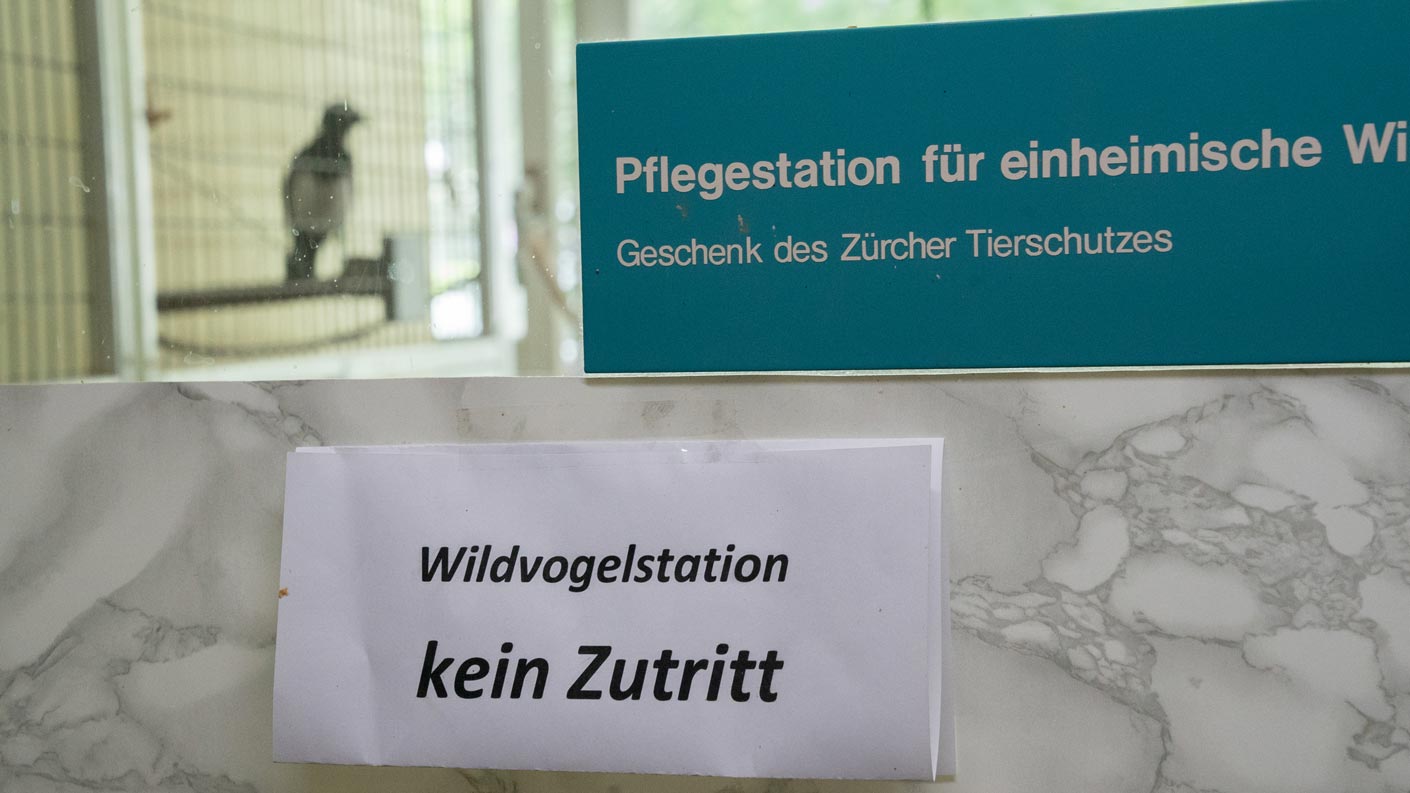

Once the birds in Elisabeth’s care are able to feed themselves, they are transferred to a centre in Affoltern am Albis that releases animals back into the wild. At this centre, the birds are carefully introduced to natural surroundings. Human contact is kept to an absolute minimum from the moment they arrive at the Voliere’s rescue station. ‘We’re just a feeding machine,’ states Elisabeth. Ravens in particular are quick to become accustomed to people and trust them. If they are set free after they establish a bond, they will not survive in the wilderness.

A channel-billed toucan that received a partial prosthetic beak

Elisabeth also receives calls time and again from people wanting to care for their new foundlings at home. However, this is a criminal offence. Raising a wild animal at home requires a permit – even for something as small as a sparrow. ‘Nature has to be protected. Imagine what would happen if everybody wanted to take a tree from the forest,’ says Elisabeth.

In Switzerland, wild birds are becoming increasingly endangered. Their habitats are continuing to reduce in size. ‘Blackbirds are now even starting to nest in shutter box units. That’s something I never used to see,’ says Elisabeth. She contends that people simply do not have much of a relationship with birds. ‘They’re not exactly cuddly toys.’ Recently, a man actually called the Voliere to ask how he could get the blackbirds to stop making noise in the morning. He lived in the city centre. ‘I just asked him whether the tram and the traffic disturbed him too.’ Elisabeth also doesn’t have any time for owners who would rather bring fledgling wild birds to the rescue station than lock their cat in the house for a week. ‘This would save so many young birds from death.’

In Switzerland, wild birds are becoming increasingly endangered. Their habitats are continuing to reduce in size.

Elisabeth has been working at the Voliere for 18 years. She initially started here to help her sister, who is a trained animal keeper, during a challenging time for the centre. Elisabeth is now the managing director. She served as the President of Voliere Gesellschaft Zürich for ten years. She has taken a range of courses to expand her knowledge about birds. During the season – which can last from March to August depending on the weather – she sometimes has to do 12-hour shifts. If she is tasked with raising an exotic bird, she will take it home with her; unlike the native birds, these exotic varieties also have to be fed at night. Elisabeth develops a strong bond with these animals. Even so, she forces herself to let them go. ‘It’s hard, but essential. After all, they aren’t house pets.’

Address

Voliere Gesellschaft Zürich

Mythenquai 1

8002 Zürich

+41 44 201 05 36

Website

Opening times

Visitor centre

Tuesday to Sunday, 10 am to 12 pm, 2 pm to 4 pm

Closed on Mondays

Emergency unit

Daily, 10 am to 12 pm, 2 pm to 4 pm

Info

Each year, the Voliere receives around 45,000 visitors, including many tourists, ornithologists, families and school classes. More than 80 birds from around the world are resident in the Voliere, which has been open to the public since 1903. The society was founded by J.J. Burkhard in 1898. The Voliere relies on contributions and donations from members and from private individuals, foundations and the city of Zurich.