From cottage industries to the home office

Doing your job within your own four walls isn’t a phenomenon of the computer age. But while the home office in most cases entails a better quality of life, the type of working from home that many people did before industrialisation was an exploitative form of working.

The concept of the home office or working from home implies, for a start, that work and living normally take place in different locations. Before the industrial age, this distinction between place of residence and place of work was irrelevant for most people. In the Middle Ages, people lived on the farm where they worked during the day. You lived at your place of work, rather than the other way round: a medieval shopkeeper slept in his shop at night, farmhands slept in the stable, and woodcutters and miners camped in huts in a clearing. Actual ‘living in a dwelling’ was the preserve of society’s upper echelons, and it was only in very few cases that these people actually held regular jobs. Even the Sun King, Louis XIV, famously used to work from his bed: the home office before home offices were even invented!

In the Middle Ages people often worked and slept in the same place, like these mining workers in a 16th-century depiction on the mountain altar in St Anne’s Church in Annaberg-Buchholz. (Picture: Wikimedia)

In the late Middle Ages, the cottage industry system developed. In addition to farming, which was mostly carried on for subsistence purposes, many families made semi-finished products at home for subsequent final processing by artisans. The farmers didn’t grow the raw materials themselves; instead, these were provided by a merchant-employer. In many Appenzell farmhouses, for instance, flax yarn and linen cloth were made for the master weavers in the towns, and families in the Zurich Oberland and the Canton of Glarus processed cotton into yarn and woven fabric.

Workers didn’t receive a fixed wage.

The ‘putting-out system’ devised later by canny merchants went even further: the urban merchant-employer not only provided the farming family with the basic materials, or even finished fabrics, but also loaned them manufacturing equipment such as looms.

The workers, which often included the farmer’s children, worked at home to produce the finished fabrics, or decorated them with embroidery. Workers didn’t receive a fixed wage, but were paid according to quality and the quantity they produced. The finished products went back to the merchants, who exported them all over the world.

Two women at work in the parlour: one at the spinning wheel, the other at the loom, about 1890. (Picture: Swiss National Museum)

View into a weaving cellar in the Canton of Appenzell Ausserrhoden. Print by Johannes Schiess, around 1850. (Picture: Swiss National Museum)

In the 18th century the system was so successful that its traces can still be seen in the architecture of the houses, such as a typical Appenzell farmhouse of that era: the weaving cellar set up in the basement guaranteed the humid environment necessary for working on cloth, and narrow windows just above floor level provided adequate light. In the heyday of embroidery, the stable provided space for an embroidery workshop with a high ceiling and large windows. The reduction in size of the stable also shows how this work done in the home turned farming more and more into a sideline.

Minimum wages for cottage industries weren’t introduced until 1940.

In the clock-making and textile industries in particular, the putting-out system was the dominant form of production. Although the workforce was not subject to direct employer control by the merchant who paid them, they were highly dependent on him. Thanks to low wages and the fact that the merchants often retained ownership of the production machines, the slightest hold-up in the production chain caused problems for the workers. Even small downturns in the order situation resulted in lost wages for those who did this sort of work in their homes – with incomes already so tight, such losses were disastrous. Exploitation and child labour were also part of the system. Minimum wages for cottage industries weren’t introduced until 1940. By then, however, the system had all but disappeared. Fully automated machines could no longer be accommodated in a farmhouse, and so after industrialisation the workers were needed for factory-based production. In 1850, 75% of Switzerland’s industrial workforce worked in cottage industries; by 1900 the figure was still one third.

Boy working at home on a spinning wheel, around 1940. (Picture: Swiss National Museum / ASL)

Girl making socks, around 1940. (Picture: Swiss National Museum / ASL)

With the advent of factories and the growing importance of financial and information flows, place of residence and place of work became increasingly remote from one another. Initially, the workers’ dwellings were just a stone’s throw away from the workplace, and usually were specially built by the factory owner to house his workers. With increasing prosperity, however, the workers emancipated themselves from life under the boss’s control. They were enticed away by the house in the suburbs, the convenient rented flat in a tower block or, later, the stylish apartment in the old town.

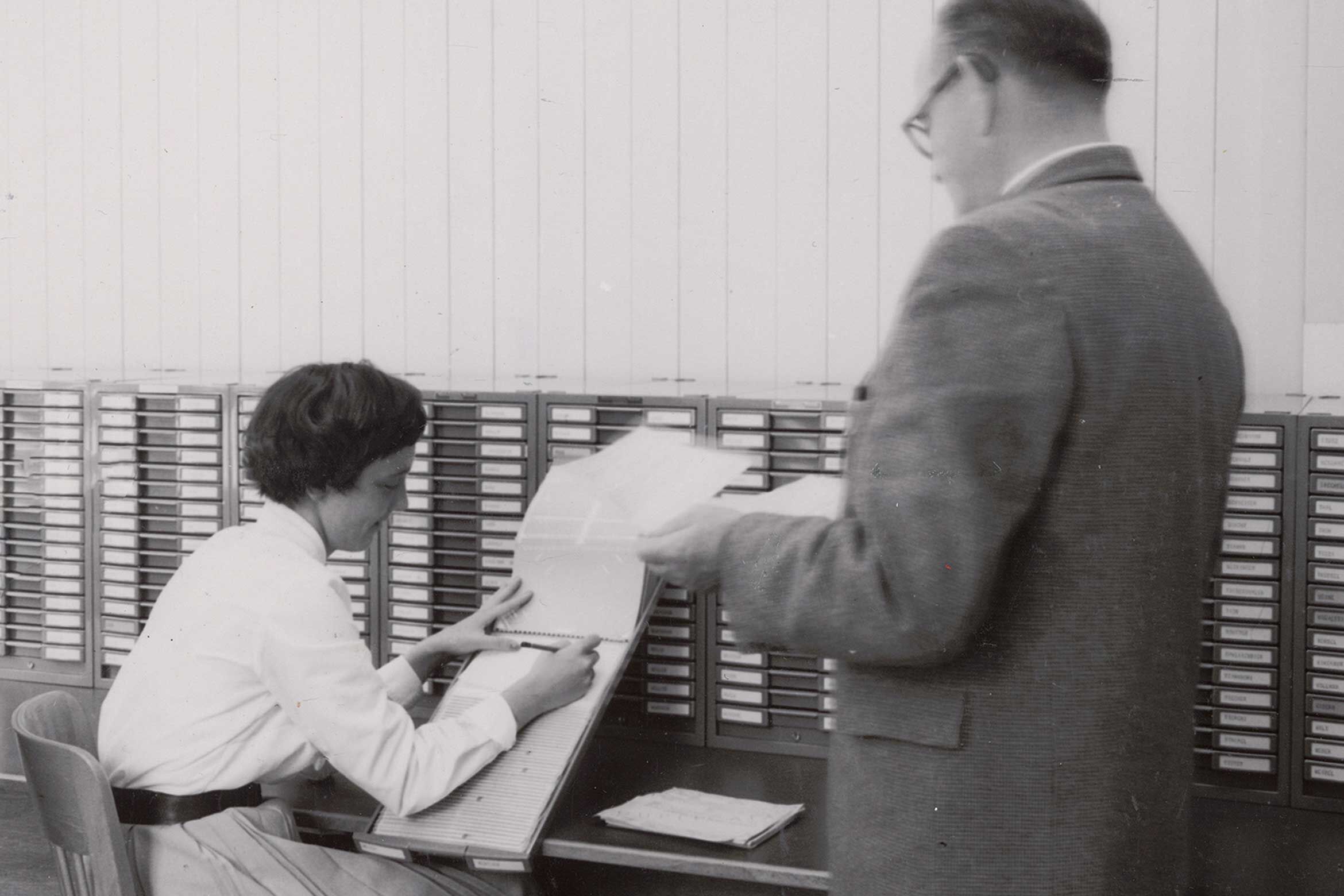

Mountains of files had to be available centrally in one place.

During the 20th century, more and more people were employed in the service sector. Before the dawn of the technology age, this sort of work necessitated an office for logistical reasons as well. Mountains of files, card indexes and papers, as well as correspondence, had to be available centrally in one place. But an administrative employee not only had to have access to stored information, but also needed to be contactable in person by supervisors. A workplace designed for efficiency was therefore essential.

A secretary at work, around 1950. (Picture: Swiss National Museum)

The coronavirus pandemic has forced many companies to look more closely at the home office concept.

The 21st-century trend towards place of work and place of residence once again having some overlap has certainly been given a boost by the coronavirus pandemic, but it had already begun with the advent of the personal computer and the internet. The first forms of what was then still known as ‘teleworking’ emerged in the 1980s. The decisive factor then was that, thanks to new means of telecommunications, employees were able to do their work from home or in a non-central office. The Schweizerische Kreditanstalt (Credit Suisse) was one of the first companies in Switzerland to experiment with teleworking. In 1989 the corporation employed 65 people at six teleworking centres in Lausanne, Lugano, Basel, Lucerne, Winterthur and Zug. While the company’s management was pleased with the results, trade unions warned of isolation and diminished employee protection.

Nowadays, it’s arguments such as reduced environmental impact through less traffic movement, greater flexibility in organising one’s working day and the better work-life balance that make the home office option attractive for workers – criteria and realities that are diametric opposites from the reality of working in the home 200 years ago. The coronavirus pandemic has forced many companies that had never previously considered it as an option to look more closely at the home office concept. While cottage industries are now history, it remains to be seen what future the home office will have.