Easy come, easy go

In 1868, Rudolf Heer and his family emigrated to America. In five letters home to his mother he described his life in the New World, allowing us a glimpse into the life of an emigrant.

In the summer of 1868, 35-year-old Rudolf Heer (1833-1882) left the city of Glarus with his family and emigrated to America. He went to seek his fortune in the New World, after letting it slip through his fingers in the old one… Unlike many of his contemporaries, Rudolf Heer had established a stable livelihood in Glarus. His mechanical workshop, which he ran sometimes with a business partner and later with his younger brother, ensured a modest level of prosperity and a degree of prestige for Heer and his family. But the great fire of Glarus, which destroyed nearly two thirds of the city in May 1861, changed all that. Not because Heer’s workshop was devoured by the flames, but because he was unable to cope with the situation after the disaster.

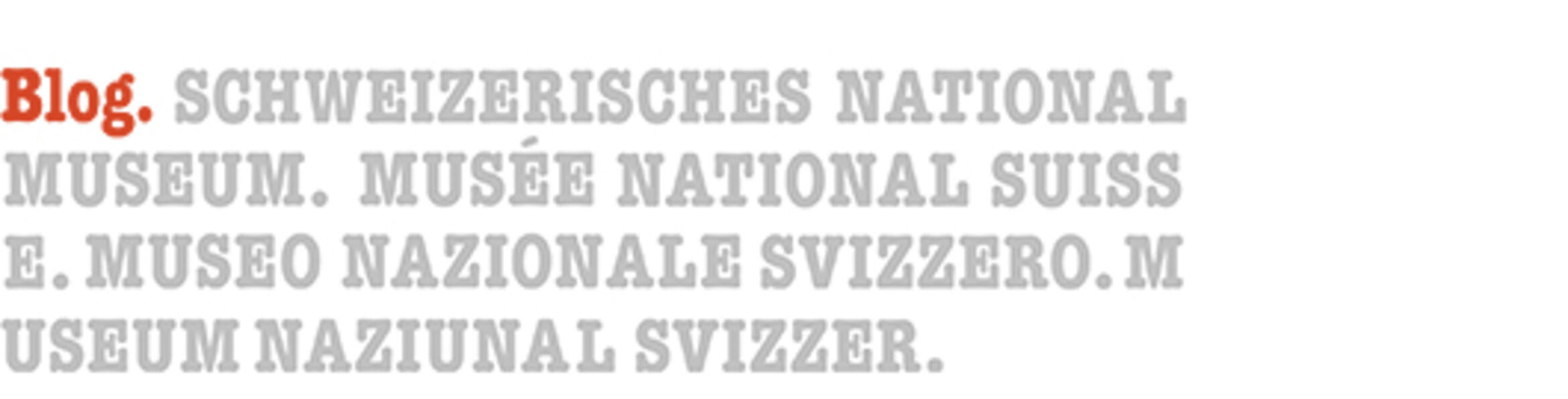

He would have been in an extremely fortunate position. Unlike those of many Glarus residents, Rudolf Heer’s house, the “Stampf”, largely escaped fire damage. Partly because the building had a solid roof of slate slabs, and partly because the mechanic had removed the wooden shutters on the night of the fire, thus preventing the flames from taking hold of the house.

The “Stampf” after the devastating Glarus fire. (Privatsammlung, Glarus)

But it got even better. Johann Caspar Wolff and Bernhard Simon were in charge of the rebuilding of Glarus. The latter had lived for many years in Saint Petersburg, where he had designed houses for scores of Russian aristocrats. The two architects planned a modern city with a chessboard layout, featuring broad streets and grand houses and squares. Not only did this require the removal of the fire debris, but the “Tschudirain”, a 23-metre mound resulting from a prehistoric landslide, also had to be dug out and carted away. Some of this rubble was dumped on Rudolf Heer’s property. He was awarded around 10,000 francs in compensation for this. A significant amount of money, considering that in those days a worker earned around 800 francs a year.

Cooperation

This article originally appeared on the Swiss National Museum's history blog. There you will regularly find exciting stories from the past. Whether double agent, impostor or pioneer. Whether artist, duchess or traitor. Delve into the magic of Swiss history.

Suddenly rich, Rudolf Heer couldn’t cope with his new life. He drank too much, gambled too much, and litigated too much. The mechanic wasn’t satisfied with the compensation provided by the municipality, and initiated a slew of costly lawsuits to try to get even more money. With the opposite effect. In 1868 Heer was broke, and the “Stampf” was put up for public auction. After his younger brother Melchior took over the building and business, there remained only one option for Rudolf: get away, as soon as possible.

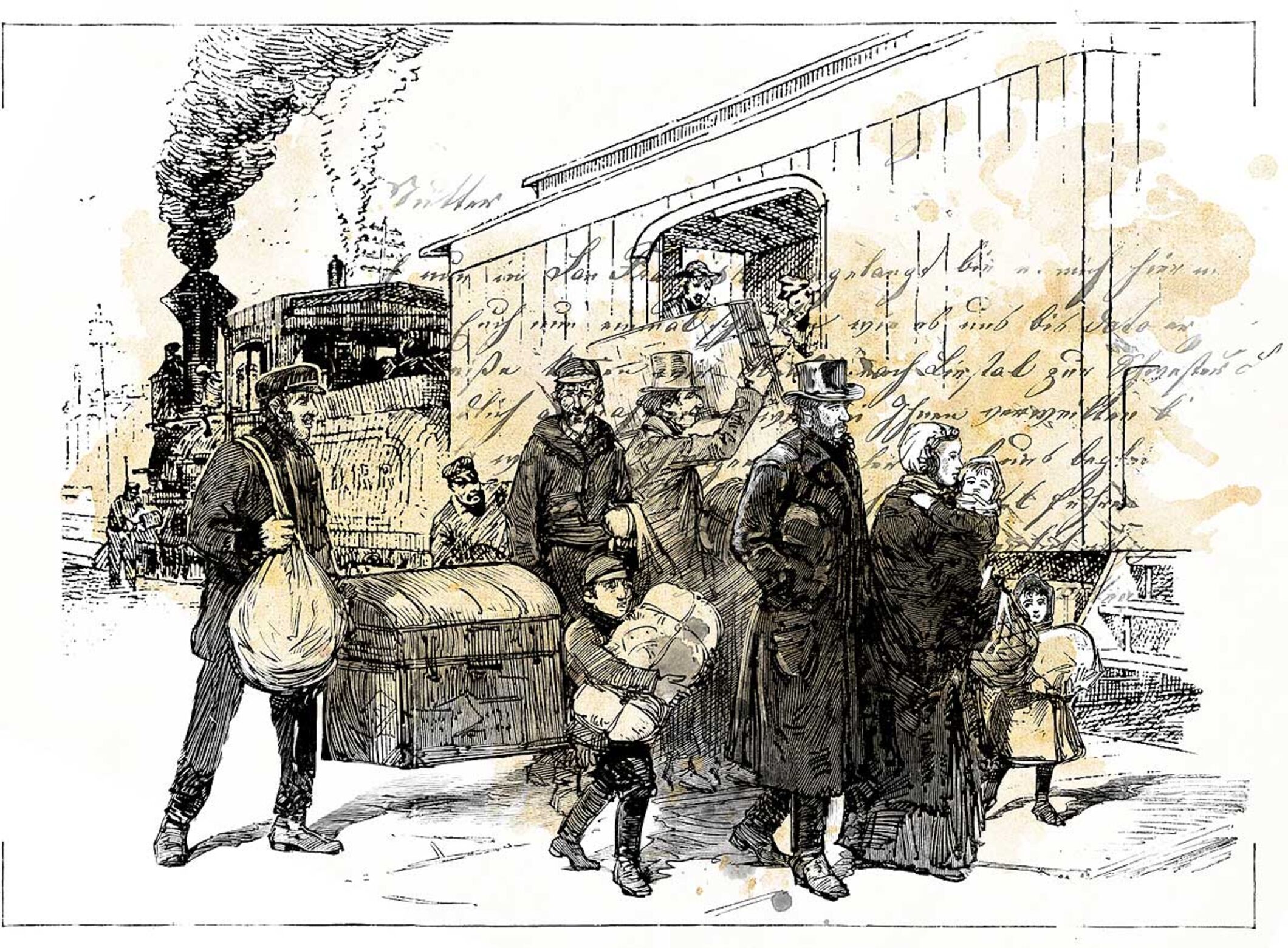

In July 1868 the Heer family left Glarus forever. Their new life led them to America via Zurich, Basel, Paris and Le Havre. (Illustration by Marco Heer)

On 22 July 1868 Rudolf Heer, together with his wife, Rosina, and their two daughters, Barbara and Maria, boarded the train in Glarus. Their long journey to America had begun. The Heers travelled with the Vereinigte Schweizerbahnen via Rapperswil and Uster to Zurich, where they had to change trains. The Nordostbahn brought them to Aarau via Baden and Brugg. After changing trains a second time, the family travelled with the Centralbahn via Olten to Liestal.

Letters from the New World

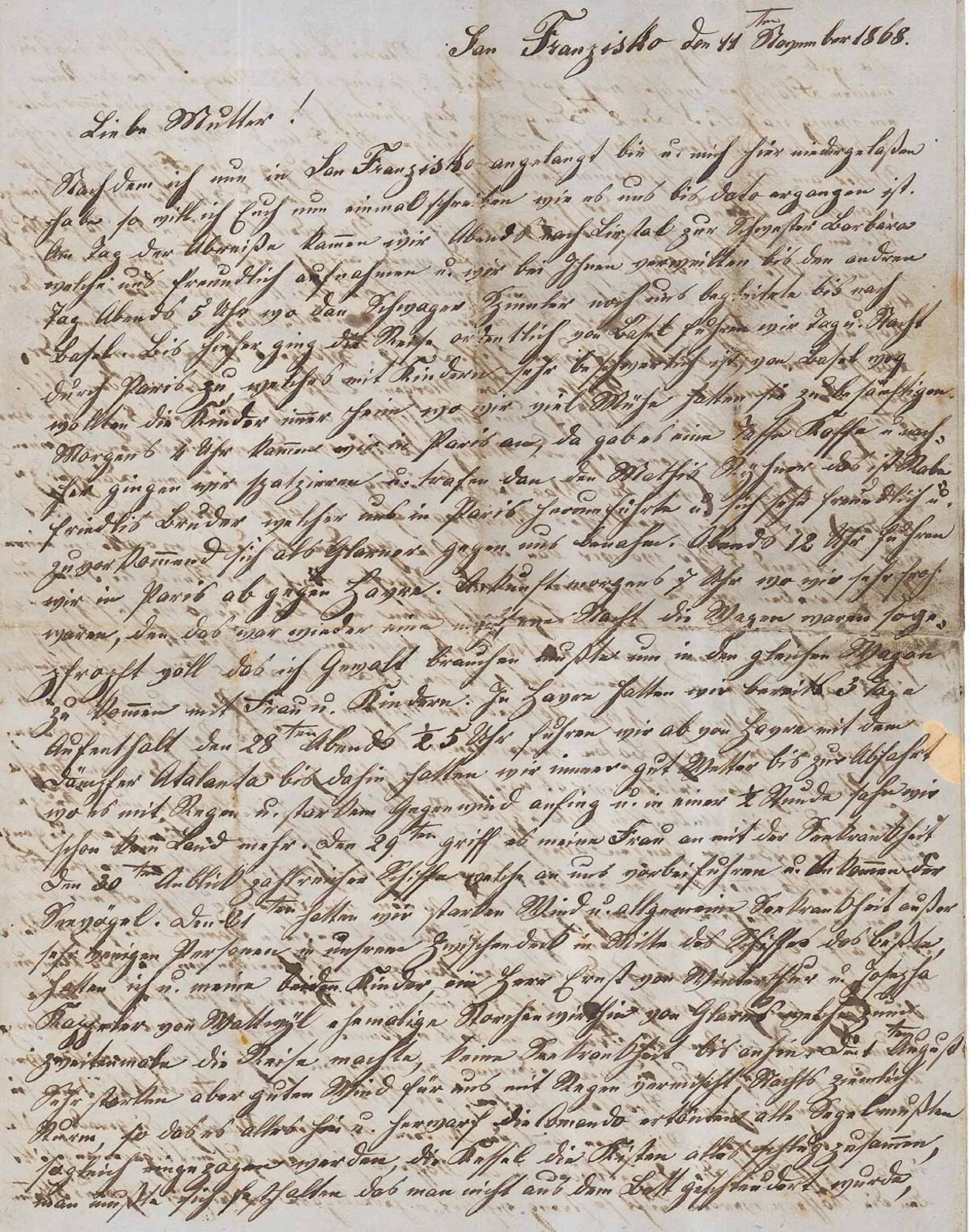

Rudolf Heer emigrated to America from Glarus in the 19th century. Between 1868 and 1872 he sent a total of five letters back to his old homeland. The letters are now in the archives of the Heer family, along with a number of other documents. This article is based on those letters and on research carried out by Fred Heer, a descendant of the Heers who stayed in Glarus.

“On the day we left Glarus we got to Liestal in the evening, to my sister Barbara, who welcomed us warmly, and we stayed with her until 5 o’clock the next day, when my brother-in-law Spinnler accompanied us to Basel. So far the journey had gone well. From Basel we travelled for a day and a night to Paris, which is very trying with the children. On the journey onwards from Basel the children were constantly wanting to go home, and we had a lot of trouble soothing them. We arrived in Paris at 4 in the morning. At 12 o'clock in the evening we left Paris for Le Havre. We arrived at 7 a.m. and were very happy because it had been another difficult night. The carriages were crammed so full that I had to use force to get into the same one as my wife and children.”

In his first letter from the New World, Rudolf Heer described to his mother the first few days of the journey. They sound stressful and exhausting, and it didn’t get any better. On the ship that was to take the family from Le Havre to New York, conditions were even tougher than in the overcrowded train compartments.

The first letter from Rudolf Heer to his mother, written in November 1868. (Heer Family Archive)

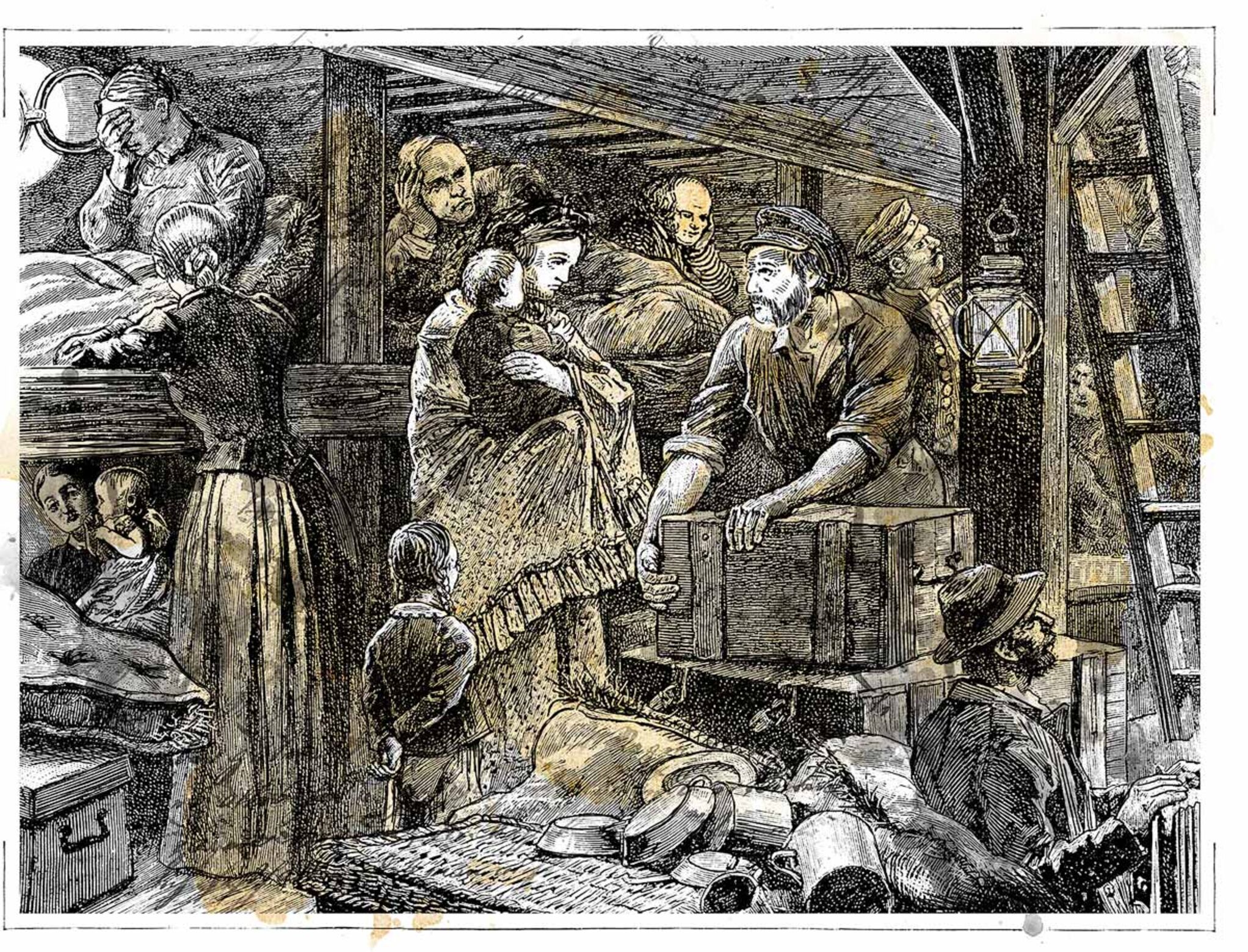

On 28 July 1868, after a three-day halt on the Atlantic coast, the family from Glarus boarded the ocean steamer Atalanta. They were among 427 passengers who made the crossing to New York. Like most of those on board, they had places in steerage. There, crowded between luggage and people, they spent most of their time in cramped wooden pens.

“On the 29th my wife was laid low by seasickness. On the 31st we had strong winds, and general seasickness, except for a handful of people in our steerage section amidships.”

There were also stormy weather conditions, which was very hard on the passengers in steerage:

“There was quite a storm at night, with everything being hurled back and forth, the order was given for all the sails to be lowered at once, the coppers and boxes were all banging together, you had to hold on so that you weren’t thrown out of bed. There was such screaming and praying – Holy Mary, pray for us. I sought solace in my bottle, which was still whole, and so it went until morning, when the storm abated a little.”

Life in steerage was hard. Rosina Heer was seasick and the days and nights spent amongst luggage items and arguing people would have felt like an eternity. (Illustration by Marco Heer)

After a minor mutiny over bad food, and constant arguing and conflicts among the passengers on the steerage deck – people from England, Scotland, Ireland, Germany, France, Italy, Russia and Switzerland were sailing to America on the vessel – on the 18th day on the high seas came the long-awaited cry: “Land ahoy!” Rudolf Heer was delirious with joy. He and his family had now been travelling for 25 days, and were setting eyes on their new home for the first time.

“On the 14th (August) at 8 o’clock in the morning we see land, a wonderfully beautiful place.”

Read here, how the Heers set foot on American soil, and soon decided to keep moving westwards.