Further into the west

After arriving in America in 1868, Swiss emigrant Rudolf Heer was unable to find work in the east of the country. So he and his family moved further west.

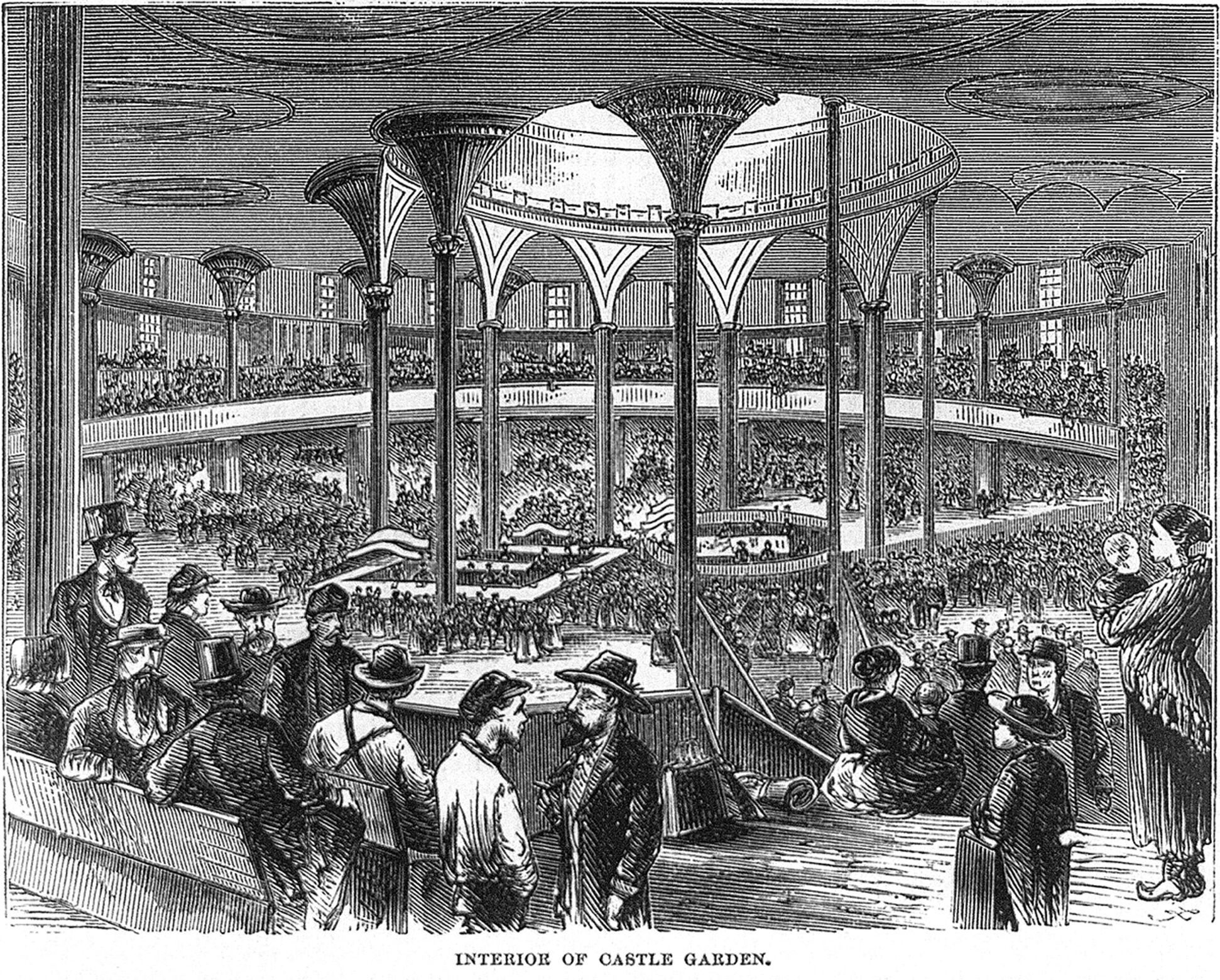

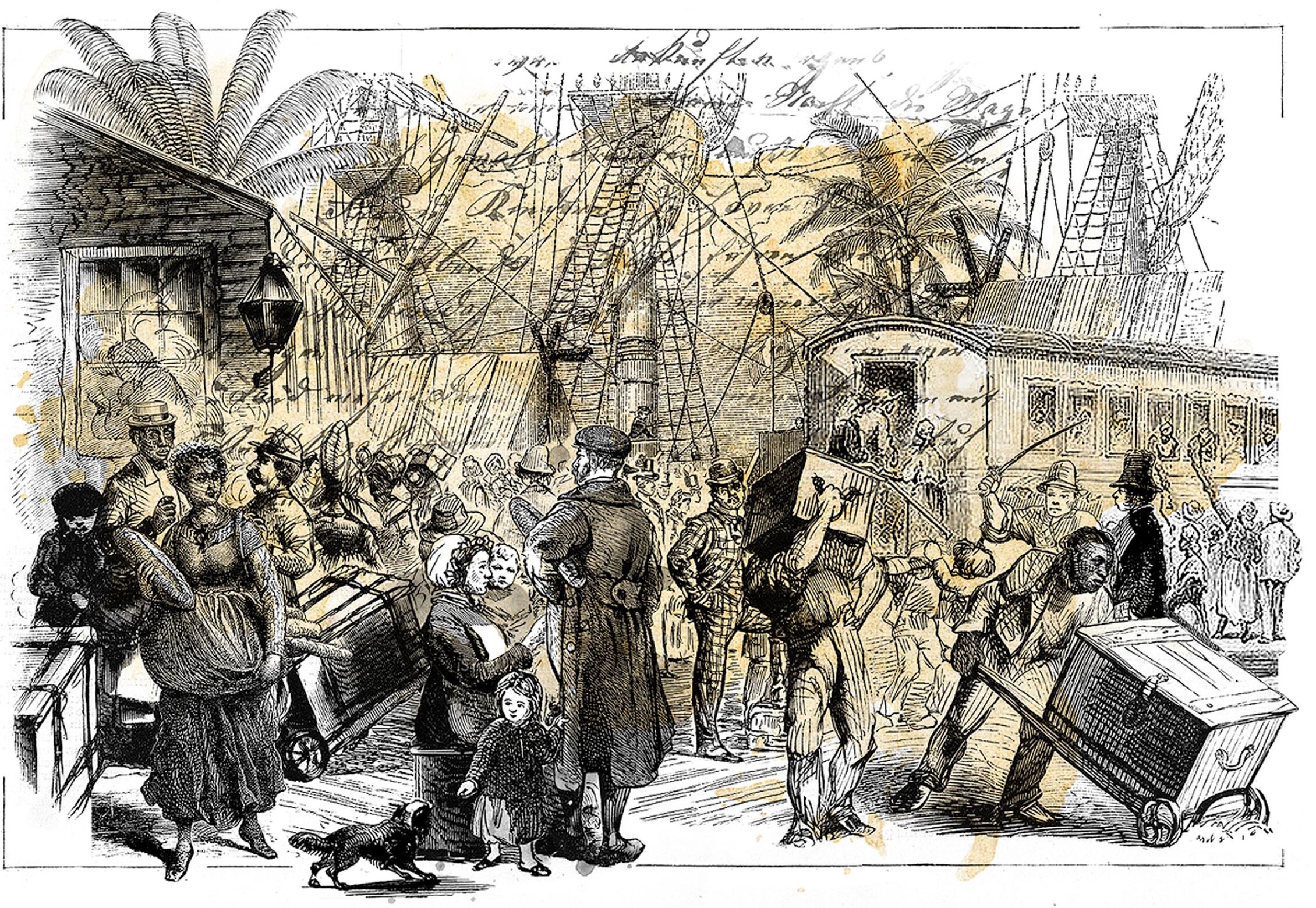

On 14 August 1868, the Heer family set foot on their new homeland for the first time, in New York. The family from Glarus were taken straight to the former artillery fortress Castle Garden at the southern tip of Manhattan. Until 1890, US authorities used the fort as a processing station for new arrivals. At Castle Garden the immigrants’ travel documents were inspected, they were given a medical examination and their luggage was searched. The search was not especially thorough, because Rudolf Heer was able to smuggle some cigars into the country, as he candidly writes to his mother:

“The double bottoms in the cases are filled with cigars, because the cases are not inspected very closely and each cigar that costs 5 cents in Glarus costs 10 cents or 1/2 a franc in America.”

The immigrants were examined and registered in “Castle Garden”. Illustration from Harper’s Magazine, 1871. (Library of Congress)

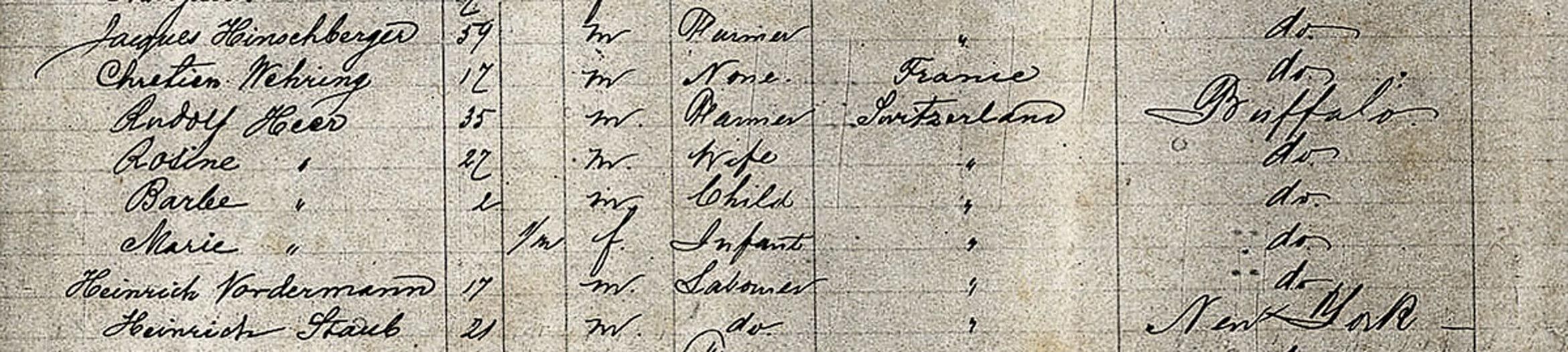

The official checks of their entry papers were not particularly scrupulous either. While Rudolf was listed as Hear on the passenger list for the Atalanta, he was entered in the immigration register under his correct surname, Heer. His wife, Rosine, meanwhile, turned into a man. Their daughter Barbara had been listed as a boy on board the ship, and remained so when she entered the country. The Heers had given Buffalo as their destination. But in the end, they never went there. The obvious suspicion is that the arriving immigrants, who often didn’t speak a word of English, had copied from one another’s papers, because a destination had to be entered on the form.

Cooperation

This article originally appeared on the Swiss National Museum's history blog. There you will regularly find exciting stories from the past. Whether double agent, impostor or pioneer. Whether artist, duchess or traitor. Delve into the magic of Swiss history.

Extract from the Castle Garden immigration register. (Library of Congress)

A few typos later, the Heer family were able to leave the Castle Garden, and took rooms at the nearby hotel Grütli. The hotel was run by the Zwilchenbart immigration agency, which had organised the family’s journey from Glarus. After just one night, the Heers continued by train to Philadelphia. David Heer, a relative of the family, had lived there since 1862. Rudolf had a letter for David from his father in Glarus, which confirms the suspicion that the Heers never had any intention of going to Buffalo. It’s more likely that Rudolf was anticipating his relative’s assistance:

“David came to us in our lodgings and told me I should stay there; he wanted to help me until I got work.”

Letters from the New World

Rudolf Heer emigrated to America from Glarus in the 19th century. Between 1868 and 1872 he sent a total of five letters back to his old homeland. The letters are now in the archives of the Heer family, along with a number of other documents. This article is based on those letters and on research carried out by Fred Heer, a descendant of the Heers who stayed in Glarus.

But despite this support, no job was found. On 25 August, Rudolf met Kaspar Jenni from Glarus, who had returned from California and now joined Heer in looking for work – a quest in which they were unsuccessful. Jenni soon began to regret coming back to Philadelphia.

“Jenni was overcome with remorse that he had left California and he sang that state’s praises in every respect, so I did some reading up about it the following night and in the morning I said to Jenni: If you want, let’s go back to California together.”

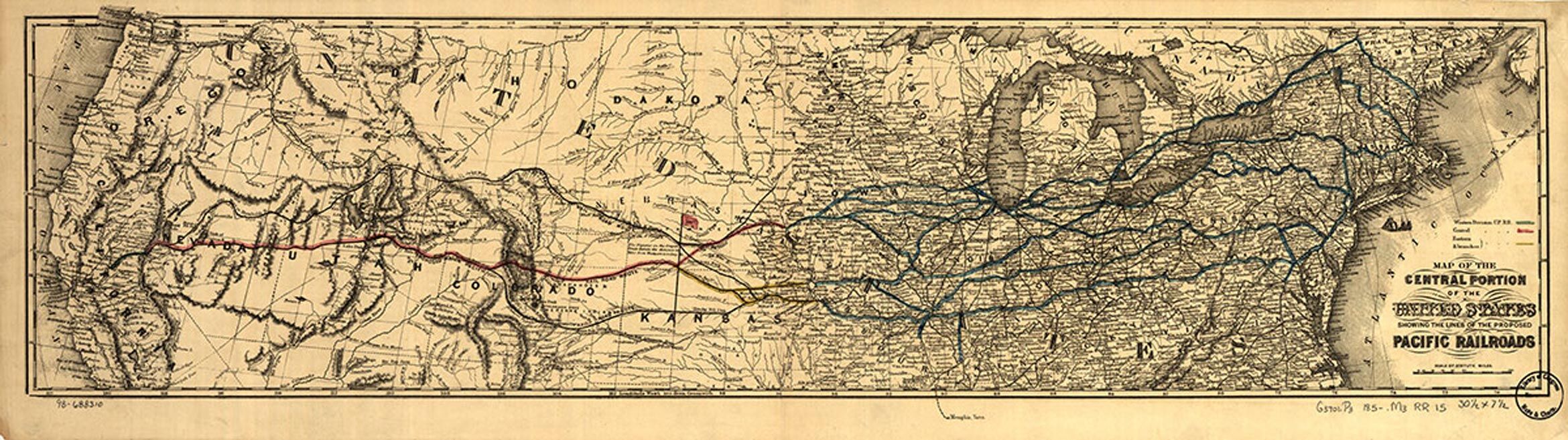

And so the Heer family, together with Kaspar Jenni, set out for California. They opted for the sea route via New York and Panama. Crossing by land would have been possible, but in 1868 the railway line ended in Omaha. It was still several thousand kilometres from there to California. The journey would have taken months and passed through a sparsely populated wilderness.

In 1868 the railway lines ended in Omaha in the west. Only a year later it was possible to travel coast to coast by train. (Library of Congress)

The journey by ship was twice as long in terms of distance, but with an approximate travel time of around one month it was comparatively fast. On 1 September 1868, the Heer family boarded the Arizona, an ocean steamer, in New York and set off southwards. To save money, Rudolf Heer passed off his two-year-old daughter Maria as an infant. On 9 September the ship docked in Aspinwall, now Colón, in Panama.

By boat to Panama and then onwards by train. In 1868 the journey to California was long and arduous. (Illustration Marco Heer)

The family from Glarus had fared badly on their second voyage. The food they were offered on the high seas was abysmal, and Rudolf immediately went in search of bread.

“Aspinwall is a small, dirty town. At the first line of houses there are pavements where the blacks hawk tropical fruits of all sorts, and fleece the passing travellers in a shameful way whenever they can. My means now consisted of just 3 paper thalers, and I have just bought bread here because we’ve been very hungry on this trip and we weren’t given any bread.”

Rudolf Heer’s mother, to whom these lines were addressed, perhaps had great reservations about banknotes or paper money, like many people in those days, and was accustomed to paying in coins. This explains why her son explicitly talks about paper thalers.

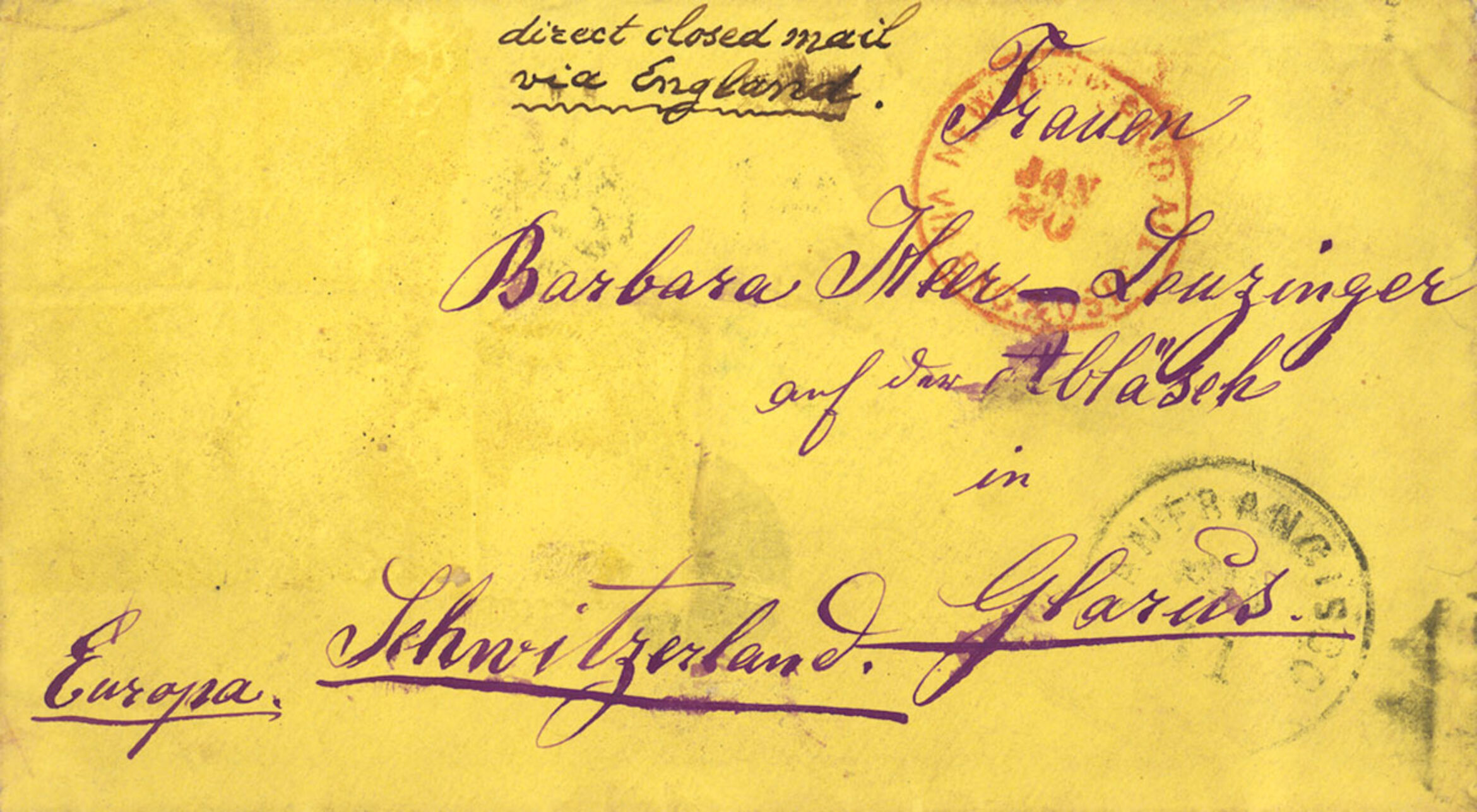

Rudolf Heer continued to write to his mother. She was his link to his old home. (Heer Family Archive)

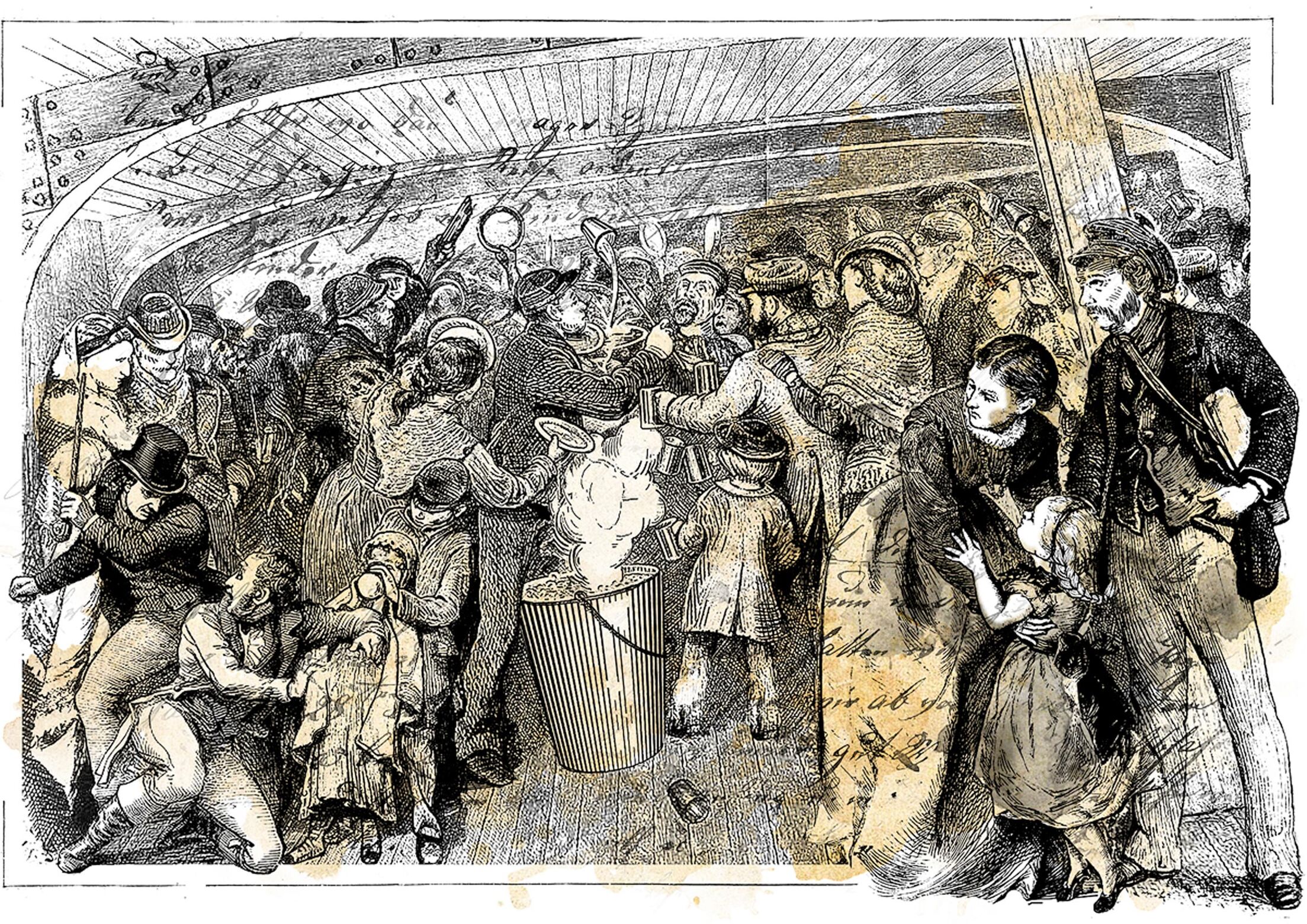

A day later, the journey continued by train. The Panama Canal didn’t exist at that time; work on its construction didn’t begin until 1881. So the immigrants had to travel from one coast to the other by train. After about three hours in a railway car packed with people, they arrived in Panama City and were immediately taken to the ocean steamer Constitution, which was to convey them to their final destination, San Francisco. For the Heers, this final voyage was the worst:

“The journey from Le Havre to New York was a pleasure cruise compared to this one, because from New York to Aspinwall we suffered from great hunger and from Panama to San Francisco it was even worse: there were no potatoes for 10 days, no such thing as bread, nothing but foul-smelling meat, sulphurated rice, Türken (polenta) and rusks and that’s all, and if you wanted to get anything you had to scramble for it.”

The daily battle for the bad food was waged with hands and feet.

“A full hour before the signal is given with a bell, people line up like wolves waiting for their prey, and as soon as the swill is set out in large containers, everyone piles in, everything by hand, and even if it’s still hot they put their hands in it to grab something.”

Food on board the boat was terrible. Nevertheless, there were daily fights for it. (Illustration by Marco Heer)

And then, on 25 September 1868, San Francisco finally came in sight. The Heer family from Glarus had reached their destination. It was here, in sun-drenched California, that Rudolf’s new and better life was to begin. He didn’t know much about his new home:

“I can’t tell you anything yet about the conditions in this country, except that high wages are paid, because a dollar is like a franc in our country.”

Read here, how the Heers’ arrival started with an earthquake, and how Rudolf finally found a job.