The power of water

The first attempts to harness the power of water date far back. Water used to provide the energy to run flour mills and looms. However, the resource only realised its full potential when hydropower began supplying the country with electricity.

In Roman times, water wheels were used in what is now Switzerland to power flour mills and water pumping stations. The wooden wheels were the only power source besides wind and pure muscle (whether human or animal). Hydropower was used for commercial purposes, such as in sawmills and forges, and in the early stages of industrialisation it powered spinning, twisting and weaving machines.

A hydropowered rye mill in the canton of Valais, 1903. ETH-Bibliothek

Hydropower proved particularly useful for Switzerland’s electricity supply. Turbines convert the water’s kinetic energy into rotational energy, which turns the turbine shafts. This rotation powers an electricity-producing generator. Hotel pioneer Johannes Badrutt (1819-1889) attended the 1878 Paris World’s Fair and was so fascinated by the electric lighting system on display that he started using a water turbine in St. Moritz that very year. The first electric light in Switzerland thus shone on 18 July 1879 in the old dining room of Hotel Kulm in St. Moritz. Electricity represented progress and prosperity. Unsurprisingly, Switzerland’s first electrically powered railway – Vevey-Montreux-Chillon – was in the tourist region of Lake Geneva. The use of electricity became more widespread when it was adopted by the larger Lötschbergbahn and Rhaetian Railway networks.

Putting up the overhead lines for the Rhaetian Railway (RhB) at Sumvitg in Surselva, 1922. Archiv Rhätische Bahn

Dependency on import

Switzerland quickly made a name for itself as something of a hydropower pioneer with a series of records: Europe’s first concrete dam in 1872 at Pérolles to the south of Freiburg, Europe’s first arch dam (Montsalvens) in 1921 and, at 111 metres, the world’s highest water barrier in 1924 in Wägital. However, coal remained by far the biggest energy source. In 1910, electricity only accounted for about 3.5% of total energy consumption in Switzerland. As Switzerland had practically no coal of its own, the country had to import. This import dependency became starkly apparent during the First World War. After the war finished, electricity consumption grew more widespread. The SBB electrified its rail lines using its own hydroelectric power plants: the Gotthard line converted to electricity with plants at Ritom (1920) in the canton of Ticino and Amsteg (1922) in the canton of Uri. As of 28 May 1922, the entire line from Lucerne to Chiasso was powered by electricity.

Cooperation

This article originally appeared on the Swiss National Museum's history blog. There you will regularly find exciting stories from the past. Whether double agent, impostor or pioneer. Whether artist, duchess or traitor. Delve into the magic of Swiss history.

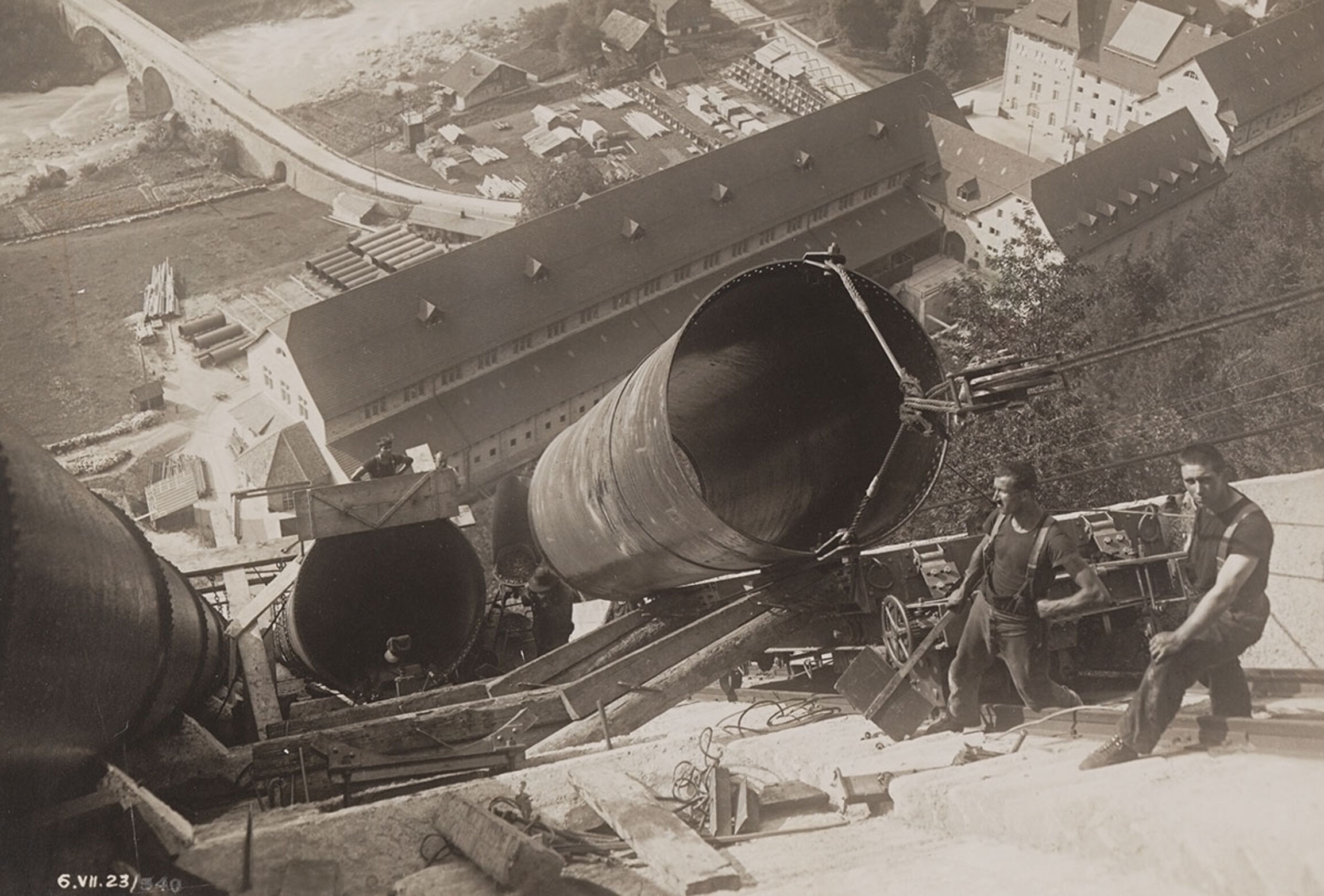

Removal of a pipe from the funicular for construction of the pressure pipe. Amsteg hydropower plant is visible in the valley below. Photo from 1920. SBB Historic

The electrification of the SBB at the beginning of the twentieth century was a milestone for the electricity sector, which was still in its infancy, and indeed for the entire country. Hydropower became a subject of national interest during the interwar period; electricity was termed “white coal” and set against the black “dirty coal” being imported into the country.

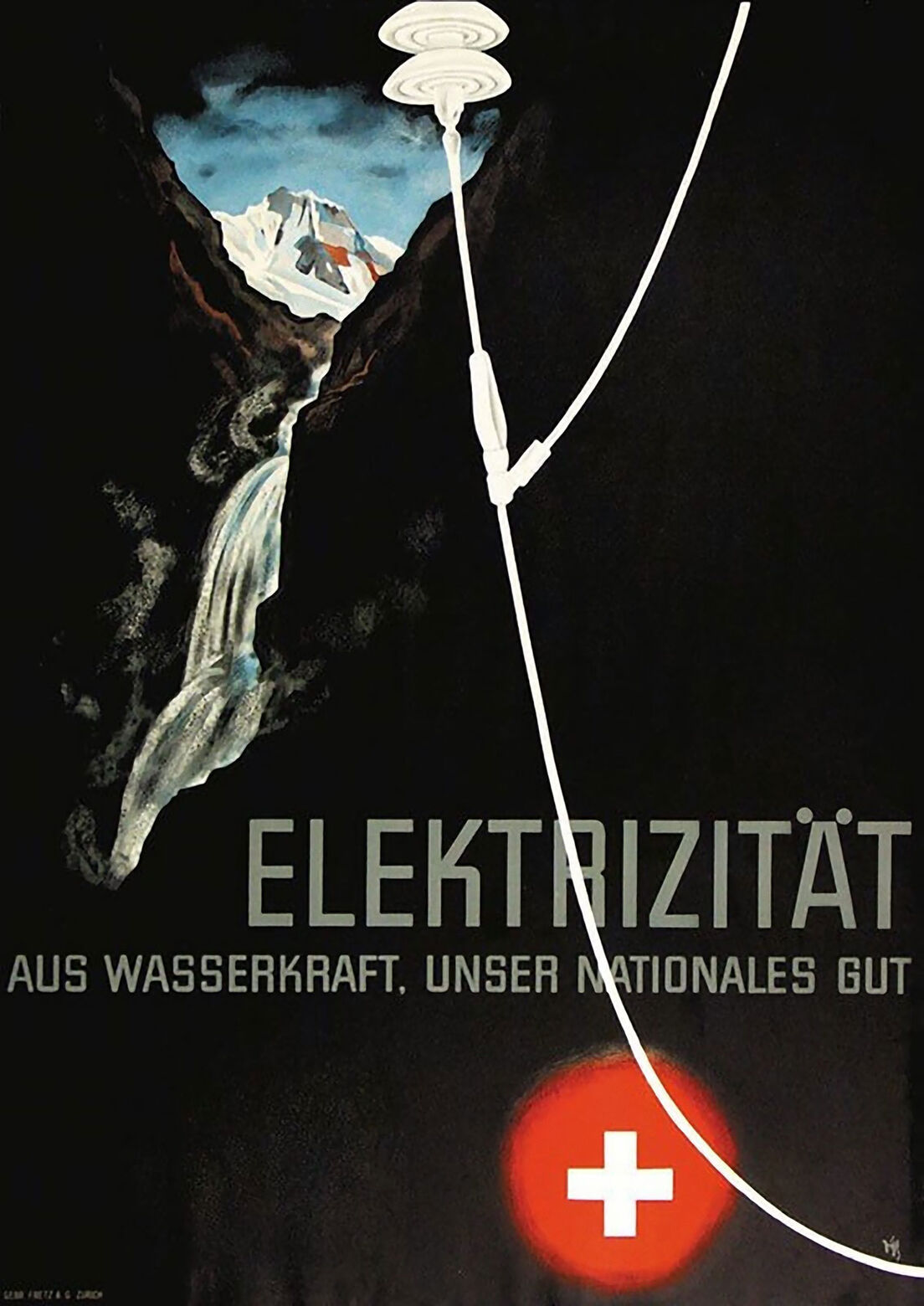

Poster by Walter Diggelmann from 1936. Switzerland is depicted as a mountain nation with a lot of water. The prominent electricity lines running over the Swiss cross look like an injection. The entire country was to be powered by the “white coal” derived from hydropower. SBB Historic

Hydropower: the Swiss myth

Demand for energy grew after the Second World War. Electricity consumption spread, and electric household goods and heating appliances became popular consumer goods in the post-war boom. In 1956, there were 17 power stations under construction in Switzerland, mainly in the Alpine cantons. The building of the new Grande Dixence dam from 1951 to 1965 in Valais was the epitome of a gigantic hydropower project and a superlative structure in many respects. The vertiginously high dam walls contributed to the creation of a Swiss myth. After the country’s image had suffered during the Second World War, hydropower gave Switzerland something to feel good about again: a small nation in the middle of Europe managed to harness the power of water, despite the natural barriers, through its numerous machine inventors and engineers and use it to meet the country’s energy needs with the most environmentally friendly energy source.

The Grande Dixence dam in Valais is 700 metres long, 285 metres high and the Lac des Dix reservoir has a capacity of about 400 million cubic metres. Photo from 1962. ETH-Bibliothek

Construction sites and workers from abroad

The implementation of hydropower projects and dam construction works called for some sophisticated logistics. Extra roads, a concrete plant, storage depots for the massive volume of materials required, accommodation and other buildings for the workers all had to be built. In the case of the Linth-Limmern power station in the canton of Glarus, cable cars had to be set up to transport the construction materials to almost 2,000 metres above sea level as it was almost inaccessible by road. Two trams were supplied by Verkehrsbetriebe Zürich (Zurich public transport operator) to ferry the workers to the building site.

Tram from Verkehrsbetriebe Zürich, a common sight until the start of the 1950s, at the construction site of the Linth-Limmern power stations in 1960. ETH-Bildarchiv

Hydropower projects were also a recurring theme in international relations. In some cases, building dam walls and accessing water sources even entailed shifting the national border – as happened with Italy in 1953 and France in 1963. The work high up in the mountains took everything the mainly Italian workforce had to give, both physically and mentally. There were also accidents. When building the Mattmark dam in the canton of Valais in 1965, an ice avalanche killed 88 people, most of whom were Italian workers.

A hotly discussed issue

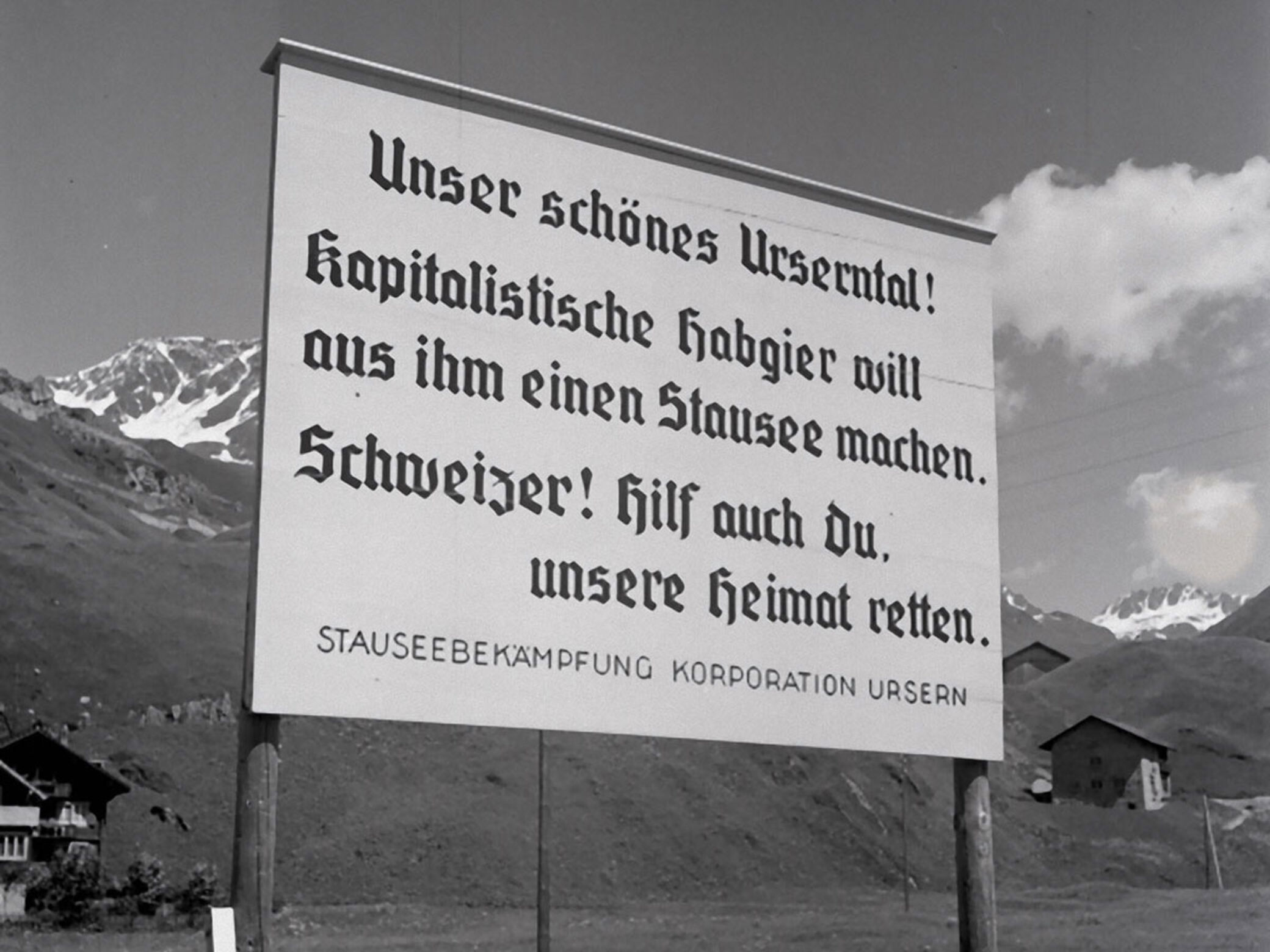

With its wealth of water, Switzerland is ideally positioned for hydropower. Nonetheless, integrating it into the Swiss energy system was anything but straightforward. It involved endless negotiations and often ended with some good old-fashioned Swiss compromise. The discussions, which became emotional on occasion, saw the two opposing camps resort to abstract ideals, such as the greater good or nature, to argue for and against hydropower projects. Some projects met with stiff opposition. In the 1940s, there were plans to construct a dam in Urserental in the canton of Uri, which would have displaced about 2,000 people living in the valley. Following peaceful protests, the gloves finally came off in a night of rioting on 9 February 1946. The enraged locals threatened to throw the lead engineer off the Devil’s Bridge and trashed an architectural practice involved in the project.

Protest sign in Andermatt against the Urseren project, photographed by Ernst Brunner, 1945/1946. Schweizerische Gesellschaft für Volkskunde

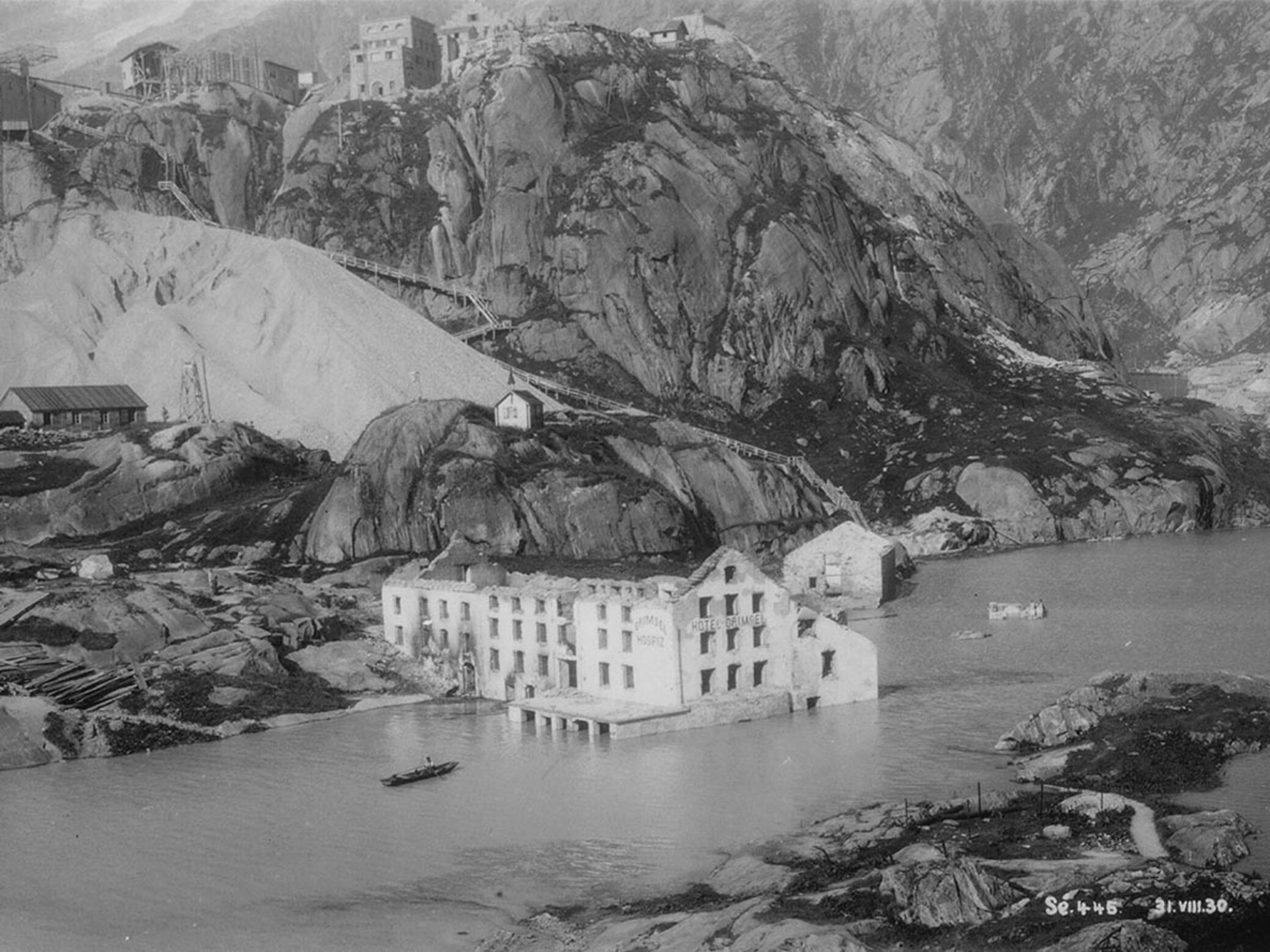

A victim of progress: the old hospice disappears to make way for the new Lake Grimsel, 31 August 1930. ETH-Bildarchiv

Following the completion of various other projects, the euphoria for all things hydro tailed off a bit in the late 1960s. Switzerland turned to nuclear power to meet its energy needs, as did many countries. Increasingly stringent environmental requirements slowed these projects down. Hydropower meanwhile remains environmentally ambivalent: nature lovers lament the spoiling of the natural beauty and loss of biodiversity. Environmental activists, on the other hand, see it as one of the most sustainable ways of generating electricity and an important instrument for climate protection. In the final analysis, reservoirs are not only reliable sources of renewable energy but also, as their name suggests, gigantic energy reservoirs and they can play a big part in bridging the winter electricity shortfall.