Switzerland’s first selfie king

A Swedish writer suffered such hard times in Switzerland that he took up photography to make ends meet – and during a stay at Lake Lucerne, he produced the first selfies.

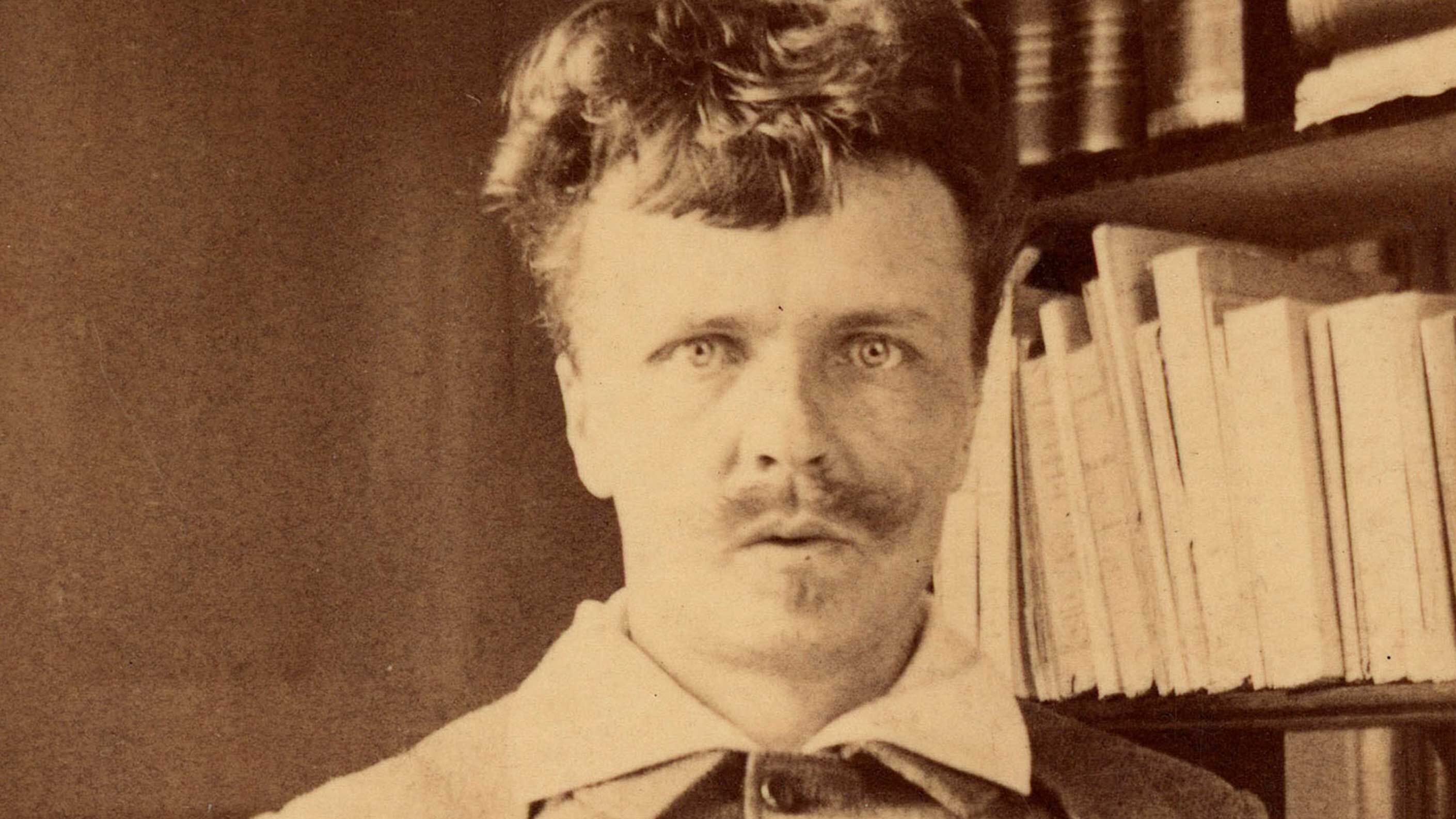

August Strindberg (1849-1912), one of Sweden’s most famous writers, spent several periods of his life living in Switzerland. The young poet jumped around a fair bit in these parts, having 22 different residential addresses within six years – no mean feat with a wife and three young children in tow!

Let’s single out a couple of the places where he lived in Switzerland: in 1884 he was residing at Lake Geneva, where he lived in Chexbres and Geneva. He was enthusiastic about the country and its people, and wrote: “I’m living in the most beautiful country in the world. Freedom! Innocence! Wonderful and vigorous thoughts! People who are free! … It is balm for the soul!” Such praise was balm for a Switzerland that at that time was quite unsettled by the growth of large nations such as Germany and Italy.

Self-portraits from his time at Lake Lucerne.

But Strindberg was a polemical figure. In his homeland, the entire print run of his novella Getting Married was impounded just days after its publication, with legal action taken against him for “blasphemy against God” and “mockery of God’s word or sacrament”. The court summoned him to Stockholm, where he had to face the charges. But Strindberg was acquitted, and his fans rejoiced.

Such praise was balm for a Switzerland that at that time was quite unsettled.

Nonetheless, the poet chose not to stay in Sweden, instead returning to Switzerland, first to Ouchy near Lausanne, where he lived in the boarding house “Le Chalet” (now Av. d’Ouchy 49). He then moved to the German-speaking part of Switzerland; in May 1886 he was living at the “Rössli” in very tranquil Othmarsingen, where his social circle included his compatriot and colleague (and winner of the 1916 Nobel Prize in Literature) Verner von Heidenstam. Von Heidenstam had taken lodgings at nearby Brunegg Castle.

Driven by an inner turmoil, Strindberg then moved on to Weggis at Lake Lucerne and in winter 1886-1887 he lived in Gersau for several months. He found accommodation at the “Gersauer Hof” inn, and was captivated: “It is wonderful to be here. Snow on the alp, herring and potatoes, schnapps, beer and lingonberries (!), and tiled stoves and interior windows.” At that time, his marriage to Finnish-Swedish actress Siri von Essen was full of conflicts and tension, which was later reflected in Strindberg’s artistic output. He gained global renown with his ground-breaking plays on relationship problems and marital crises, circumstances with which he was well acquainted from his own experience.

He devised a self-timer for his camera.

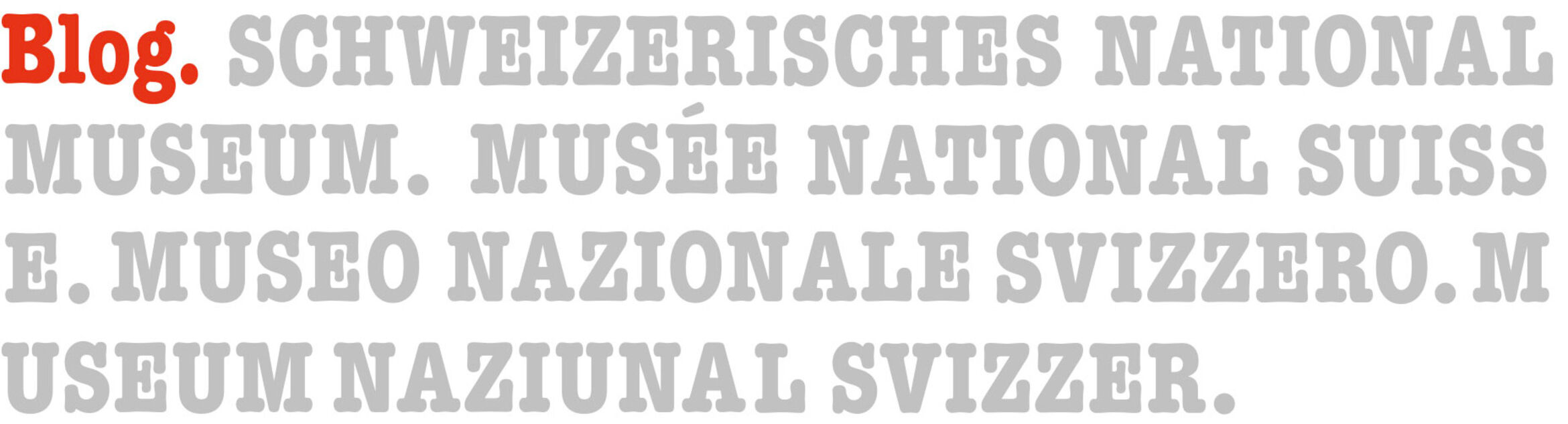

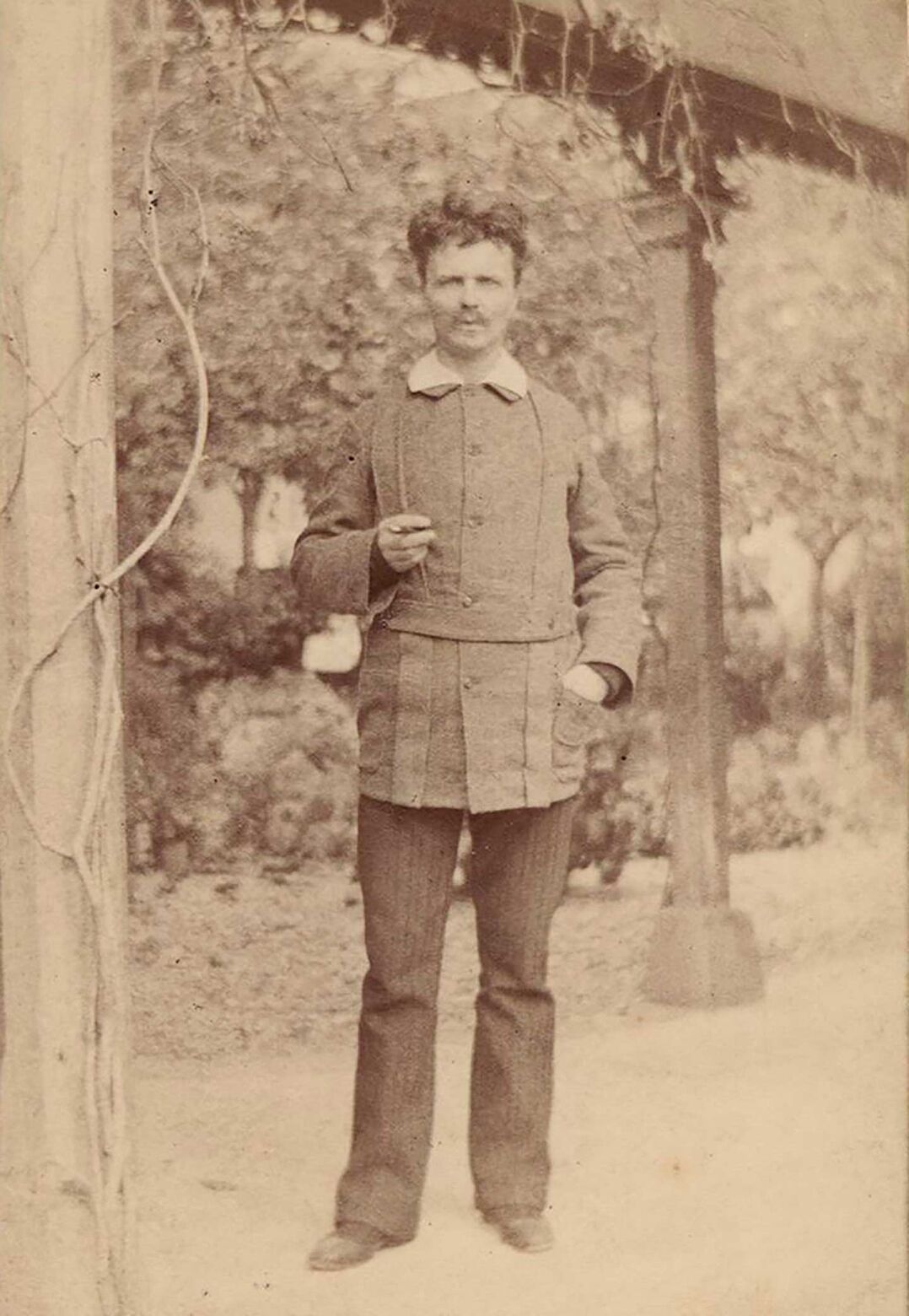

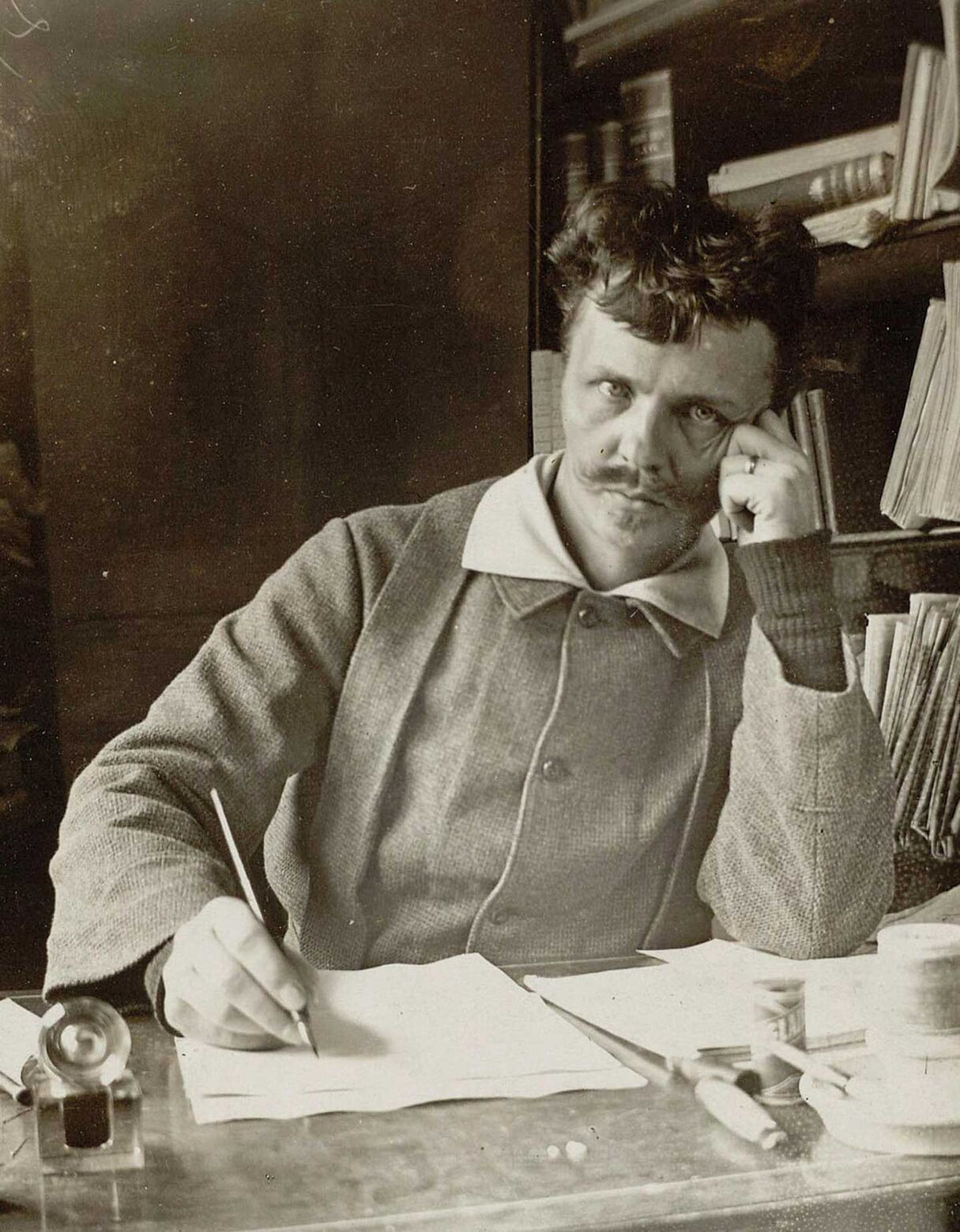

Strindberg was plagued by money troubles in Gersau, and as a constant seeker for work he began experimenting with photography. A recent innovation at the time was photographic cameras with industrially produced, ready prepared dry plates, which simplified and popularised photography. But Strindberg didn’t stop there, instead trying out new things: with the aid of a flexible tube, he devised a self-timer for his camera. In winter 1886, the poet succeeded in photographing himself – he took scores of selfies, some of which are now in the holdings of the National Library of Sweden. The selfie reproduced below shows Strindberg on the balcony of the “Gersauer Hof”; he is wearing a warm coat and a high cap in the style of a Russian exile, and his hands are buried in his coat pockets; the steeple of Gersau’s St Marzellus church can be seen in the background. Strindberg’s expression is a little tense, probably because he didn’t quite trust his self-timer mechanism. In the pictures where he shows himself at his desk, we see a pensive, frightening or even startled-looking writer.

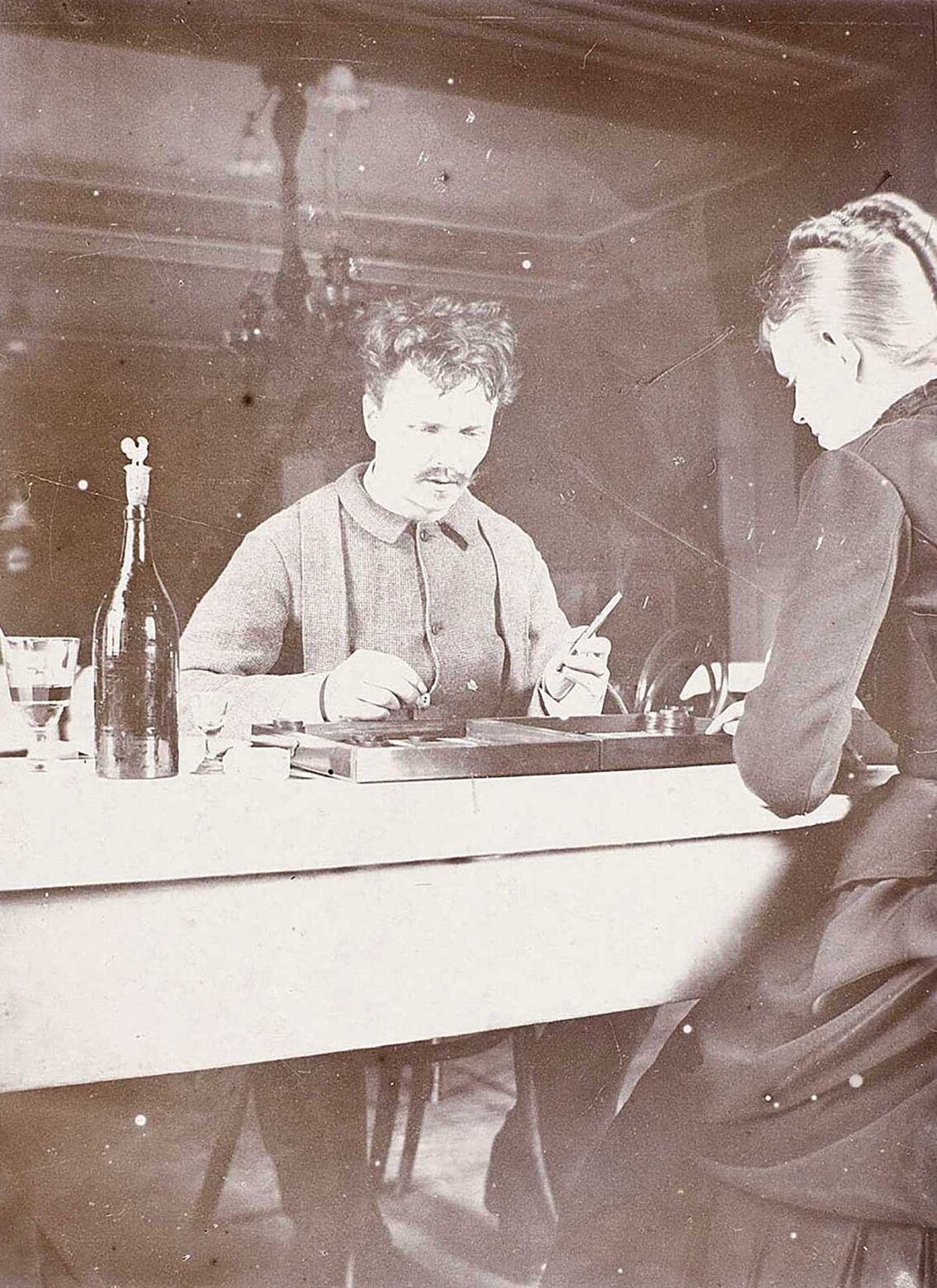

Self-portrait with his wife Siri in Gersau, 1886.

The American Robert Cornelius created a photographic self-portrait as early as 1839.

When it says in the Gersau museum of local history and in the local newspaper that Strindberg invented the selfie, that’s a very broad interpretation. The American Robert Cornelius created a photographic self-portrait as early as 1839, and in 1840 Frenchman Hippolyte Bayard even took a staged photograph of himself posed as a drowned man! Back then, no special trigger was needed because the exposure time was 10 minutes, and as a photographer you could scurry back and forth. Standardised self-timers as we know them on cameras today only became available in 1900, and from that time onwards there can scarcely have been a funfair or carnival that didn’t feature a photo booth for self-portraits. But Strindberg was a pioneer because he made and successfully used an automatic-release device as early as 1886.

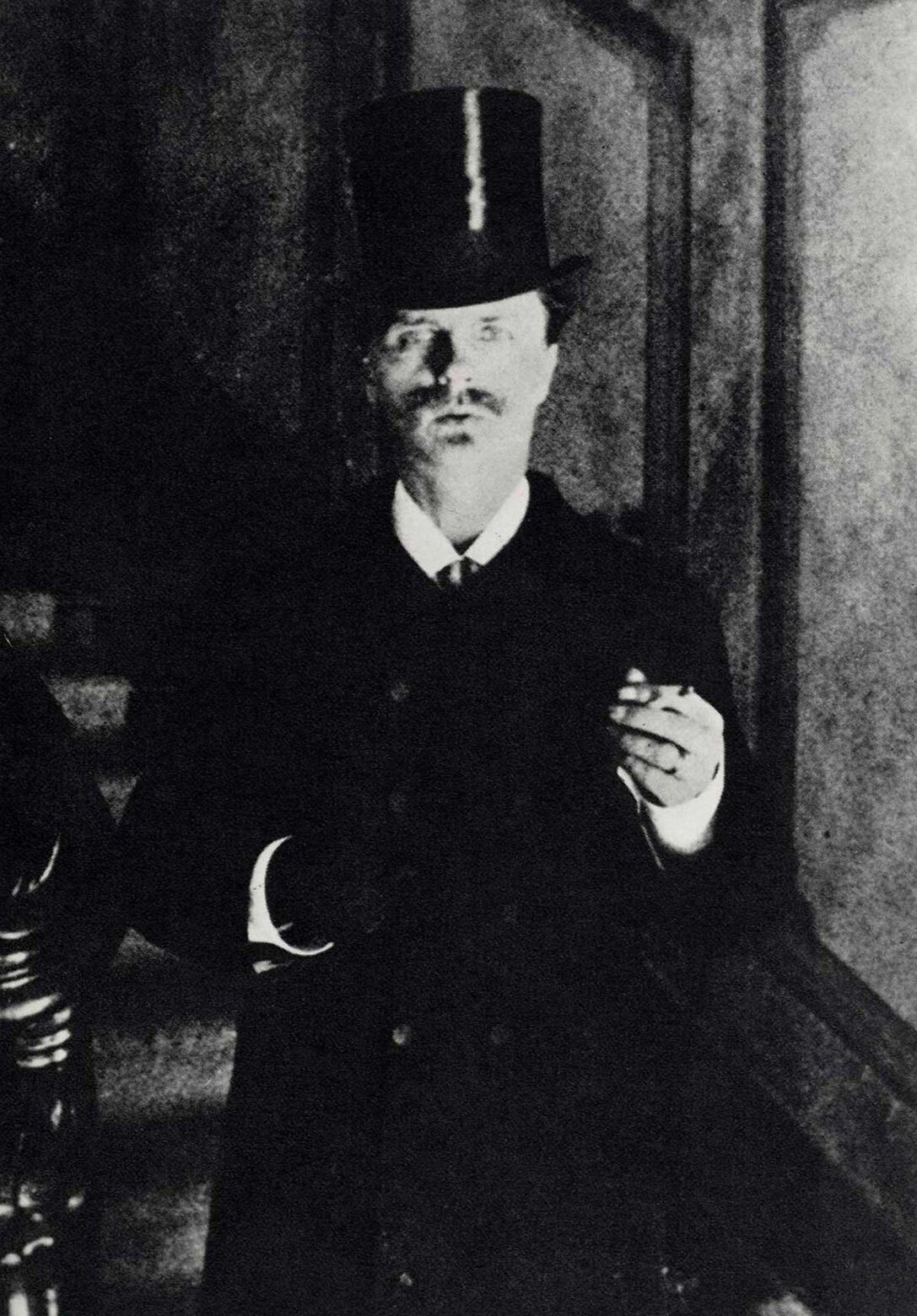

Strindberg on the balcony in Gersau.

Strindberg actually intended to publish the photographs as accompanying elements in his books. But the production costs for that sort of experimental photo printing were too high. He tried to persuade his Swedish publisher, Albert Bonnier, to bring out his Gersau Album as a separate book; however, Bonnier had no interest in his author’s visual self-reflection.

Strindberg’s publisher was more interested in his writing than in his photographs.

So Strindberg used his Swiss years as material in the “Swiss stories”, in which he depicted an idealised view of the country and his experience there: “Why are the people here in this beautiful country more peaceful? Why do they look happier than elsewhere? They do not have this schoolmaster standing over them every hour of every day; they know that they themselves have chosen who shall govern them; – Switzerland is the little miniature model on which the Europe of the future will be built.”

Strindberg went even further, suggesting that the whole world be “Swissified”, because: “To be a man is more than to be a European. You cannot change your nation, because all nations are enemies and one does not go over to the enemy. The only thing left is to neutralise yourself. Let us become Swiss!” Even though he was constantly moving from place to place and never seemed inclined to settle anywhere permanently, he had happy memories of his time in Switzerland. About ten years later he wrote: “My stay in Switzerland was like a years-long summer.”