Switzerland’s first photographer

Over 180 years ago, Switzerland’s first photographer, Johann Baptist Isenring, wowed the public and newspapers with his picture and took the oldest existing photograph of Zurich. Although Isenring was one of the best-known and most prolific photographers of his time, very few of his pictures still exist today.

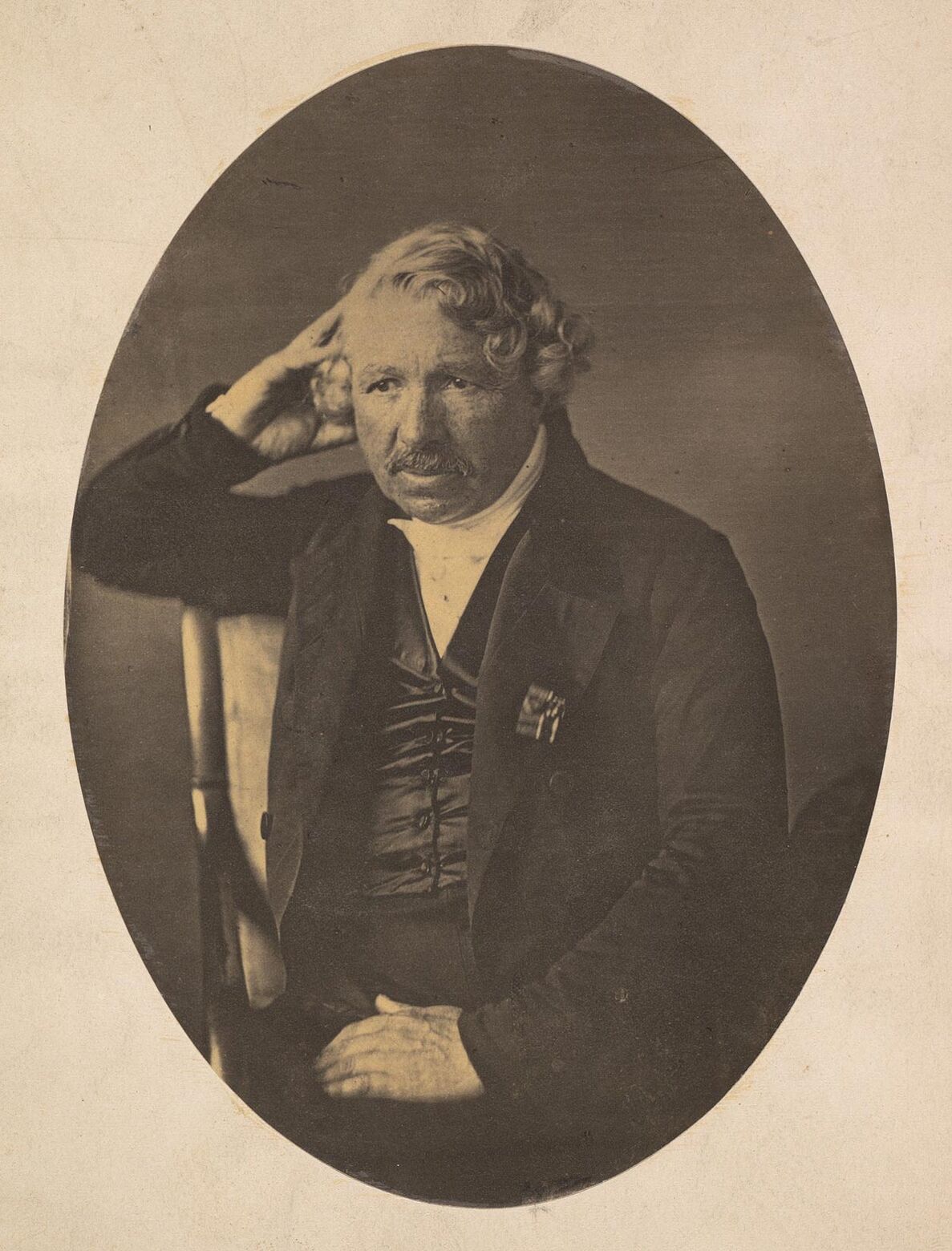

The discovery made by Frenchman Louis Daguerre in the 1830s caused a sensation. While others had already been working on recording the images from a Camera Obscura, Daguerre was the first to produce convincing pictures in sharp focus. Men of science quickly hailed the invention “major, momentous and of great consequence” as Johann Baptist Isenring (1796-1860) later wrote.

From group engravings to photography

Natural scientists were particularly impressed by this new process, which was presented to the French Academy of Sciences in Paris in August 1839. The Academy’s president, physicist and astronomer François Arago, subsequently persuaded the French government to purchase Daguerre’s patent and make the technique available to the public. Daguerre received a lifelong pension and in return, detailed descriptions of daguerrotype – as the photographic process would later be called – were released later that year.

Louis Daguerre, taken circa 1860. Wikimedia / Metropolitan Museum of Art

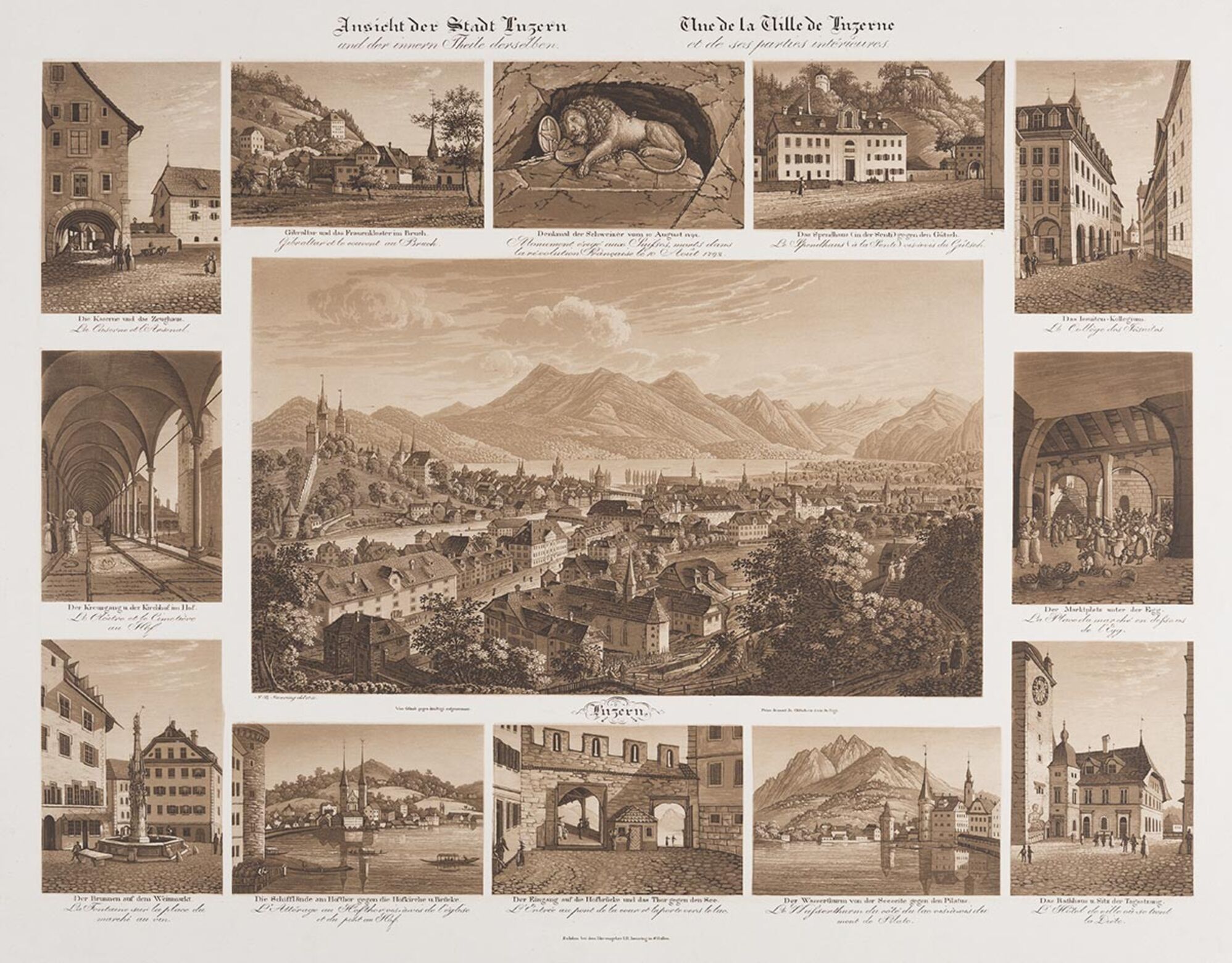

In Switzerland, Johann Baptist Isenring was the first to try it out. He had already made a name for himself as a painter, illustrator and engraver and operated an art publishing house in St. Gallen. He had notably published a huge collection of ‘picturesque views of remarkable towns and villages in Switzerland’. Isenring presented so-called group engravings – featuring a large picture in the middle, surrounded by twelve smaller pictures – depicting some 30 locations in Switzerland.

Group of engravings of the city of Lucerne by Johann Baptist Isenring, circa 1832. Schweizerisches Nationalmuseum

But from then on, he was solely interested in daguerrotype. The new process was unveiled to the public in mid-August 1839 and by November, the St. Galler Zeitung newspaper reported: “Intrepid Swiss painter Isenring has spared no expense or effort in obtaining new daguerrotypes from Paris, and in procuring the equipment to produce such images himself.” Isenring had also gained initial experience with another photography technique, that of William Henry Fox Talbot. Talbot used light-sensitised paper as a substrate, while Daguerre used silver-clad copper plates.

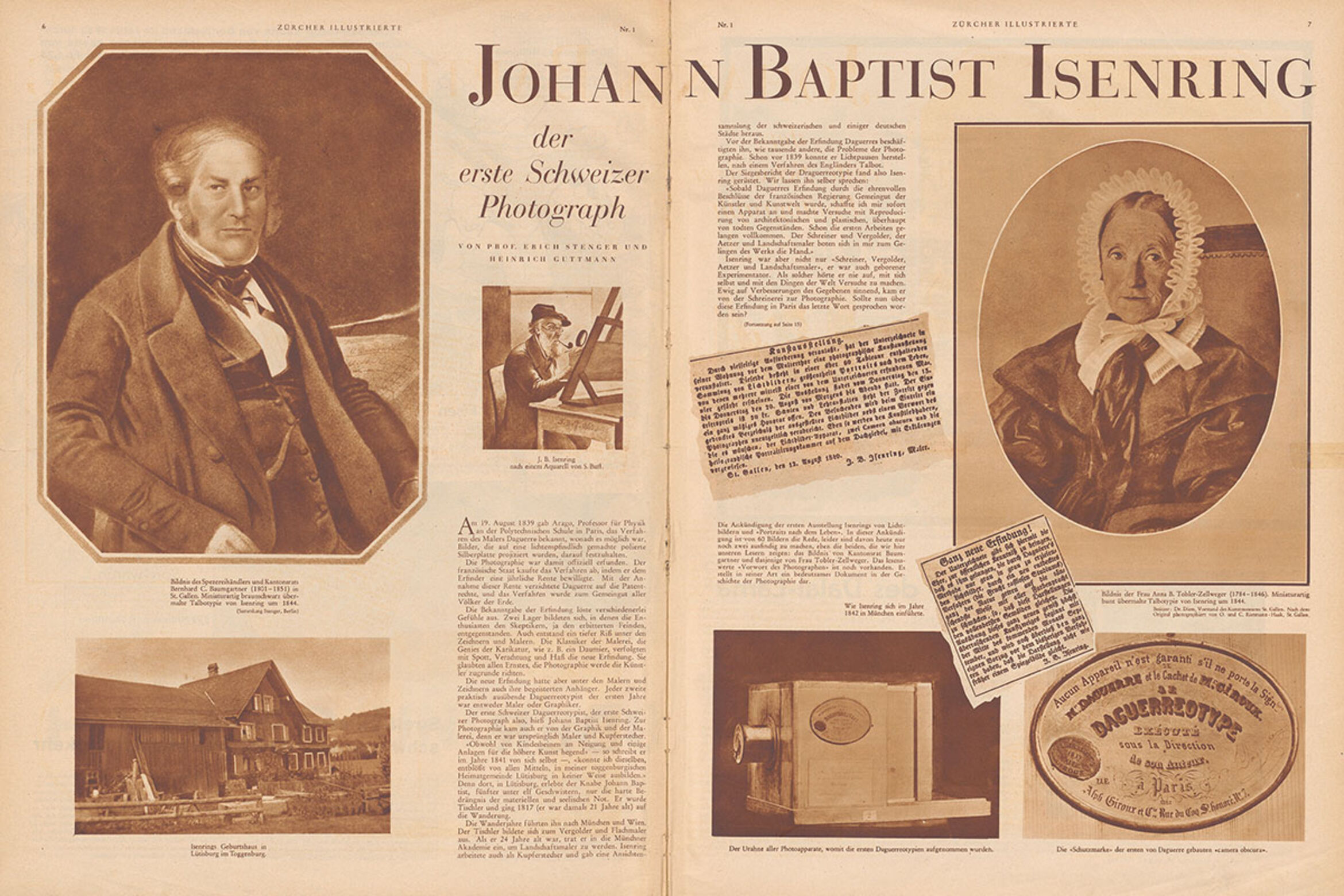

Artikel über Isenring in der Zürcher Illustrierten, Januar 1934. e-periodica

Sitting still for a quarter of an hour?

Isenring immediately set about improving daguerrotype. He started by photographing a row of houses in St. Gallen, and then the collegiate church. With an exposure time of almost a quarter of an hour, portraits initially seemed impossible. But Isenring managed to drastically reduce the exposure time and he would simply retouch the blurred eyes caused by blinking. The fact that Isenring had a very diverse training background benefited him. As he said himself: “The carpenter and gilder, the engraver and the landscape painter helped make this work a success.”

Cooperation

This article originally appeared on the Swiss National Museum's history blog. There you will regularly find exciting stories from the past. Whether double agent, impostor or pioneer. Whether artist, duchess or traitor. Delve into the magic of Swiss history.

Isenring was not only Switzerland’s first professional photographer, but also the first to organise a photo exhibition and have a detailed accompanying catalogue printed. In August 1840 he presented the exhibition comprising 47 pictures in St. Gallen, and then later in Zurich, Munich, Augsburg, Vienna and Stuttgart. The exhibition included portraits, some of which were life-size, and a number of coloured pictures.

Isenring became famous and the media – which he skilfully supplied with information – were excited. For example, the NZZ newspaper wrote the following about his exhibition: “Isenring’s pictures are so true to life in their contours and shading, they achieve an effect that is beyond even the most skilled artists.” Needless to say, the artists themselves were less keen, and were positively disparaging about the new art form. Isenring shrugged this off as “mediocre artists” defending their livelihoods.

Group portrait based on photogenic drawing by Johann Baptist Isenring, 1839. Schweizerisches Nationalmuseum

In 1841, Isenring opened a studio for heliography in Munich, and at the same time, travelled through Switzerland and southern Germany in his mobile photo lab, which also served as his bedroom and study. The vehicle, which he called the Sonnenwagen (‘sun car’) would travel from place to place. Photo advertisements were published in local newspapers to announce its arrival and people were invited to come and have their portrait taken by Isenring, or have objects photographed.

Isenring was subsequently invited to royal houses; he even presented his portrait collection to the King of Württemberg in person, as reported in the St. Galler Zeitung in May 1841: “The court was so impressed that Isenring was immediately commissioned to produce portraits of His Imperial Highness Prince Friedrich, the Count and Countess von Beroldingen, the Barons of Gemmingen and others.”

Double portrait, produced by Johann Baptist Isenring, circa 1845. Schweizerisches Nationalmuseum

Where are the daguerrotypes now?

From the mid-1840s, Isenring shifted his focus back to drawing. Evidently, the competition among photographers had become so great that the print business regained its appeal. The other advantage of prints was that they could be reproduced in large numbers. Daguerrotypes were one-off pieces – and at first were laterally reversed (mirror images). Roland Wäspe, former director of the Kunstmuseum St. Gallen and author of the definitive book on Isenring’s print works, also suspects that, by stepping back from photography, Isenring sought to allow his stepson to get off to a more successful start with his own publishing house.

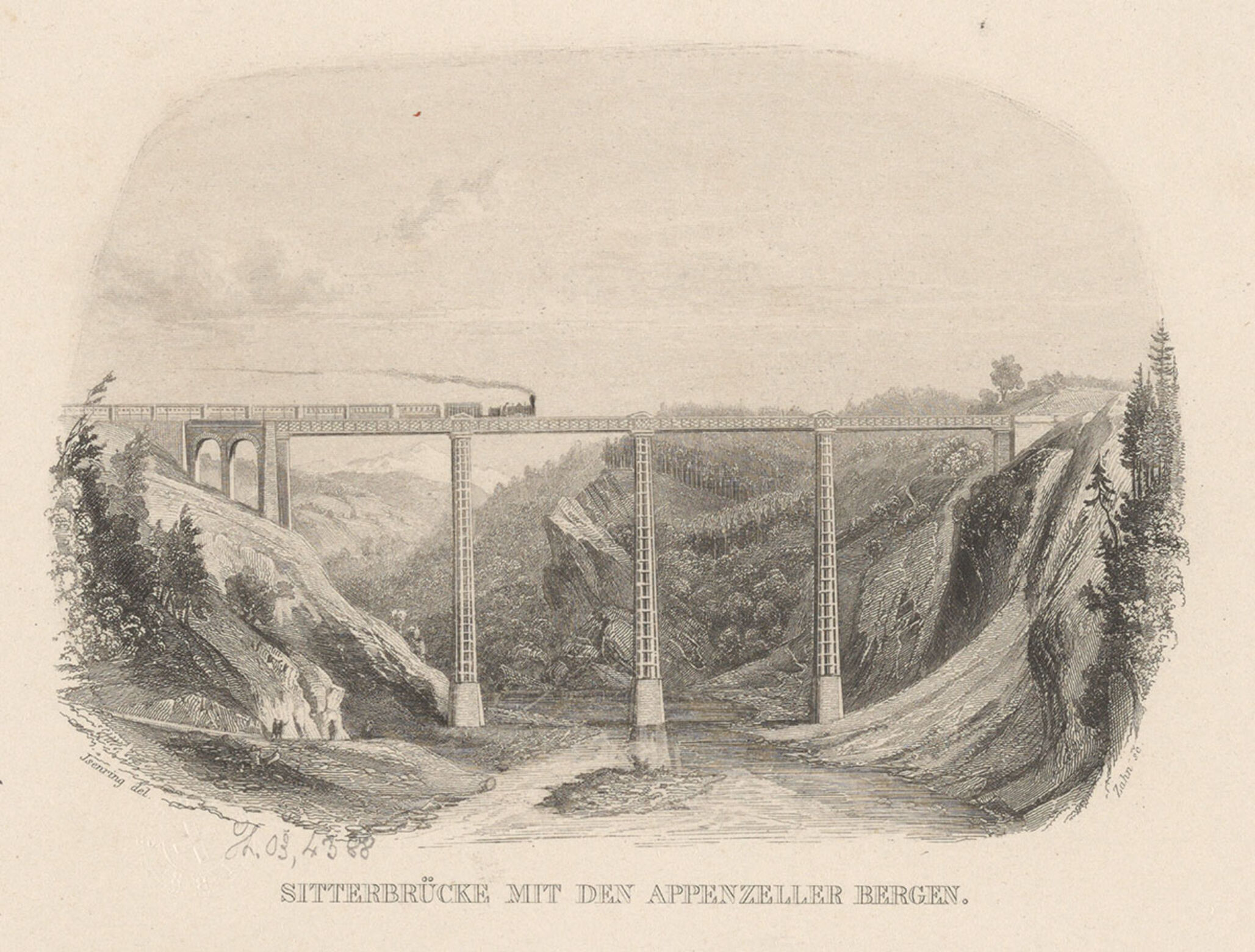

For a time Isenring continued to do photography and printing on the side, but in 1854, he decided to dedicate himself fully to his earlier profession of engraving. Only a small number of Isenring’s pioneering photographs still exist today. We can only speculate on what happened to the countless others. Perhaps he disposed of some of them himself when he no longer needed them.

Sitterbrücke and the mountains of Appenzell. Print by Johann Baptist Isenring, 1856. Wikimedia / Schweizerische Nationalbibliothek

In fact, Isenring used some of his daguerrotypes to produce templates for prints. The fact that the daguerrotypes were mirror images was not a problem as engravers could transfer them precisely as they were and produce a picture that was no longer laterally reversed. Isenring even noted on some of these images that they were originally daguerreotypes. For example, some of his city views, such as those of the Zurich Grossmünster and of the buildings around Paradeplatz, bear the inscription: ‘Photographed by publisher J.B. Isenring’. Some of these images are kept in the Zürcher Zentralbibliothek. But we don’t know whether Isenring kept the original photos.

The oldest photo of Zurich

The Sammlung W. + T. Bosshard is considered the most important collection of daguerrotypes in Switzerland. The collection also comprises some pictures by Isenring, including a shot from 1844, which is thought to be the oldest surviving photograph of Zurich. While the picture is not signed, photo historian René Perret is convinced that it is one of Isenring’s – Isenring himself and his son even feature on the edge of the picture. It shows the old post office close to Paradeplatz, which was later converted into the Zentralhof.

The oldest existing photograph of Zurich is by Johann Baptist Isenring. It depicts a mirror image view of the old post office building with Paradeplatz in the background. Sammlung W. + T. Bosshard

Incidentally, only recently, Werner Bosshard was able to add a daguerrotype from his collection, which shows Isenring and his son. The rare image is being published here for the first time.

Johann Baptist Isenring died in 1860, just three months after his wife. Several days after his death, the Tagblatt der Stadt St. Gallen newspaper published an obituary and detailed tribute to Isenring as a painter, publisher and photographer: “Through tireless hard work and without any external assistance so to speak, the painter Isenring worked his way up to a level that later earned him recognition from far and wide.”

However, as a pioneer of photography, Isenring was soon forgotten. New photographers and new techniques overshadowed the pioneer after he stopped producing photographs. It was not until 1931, when collector and historian Erich Stenger organised a collection of source material that Isenring’s important role was recognised once again.

Neu aufgetauchte Daguerreotypie des jüngeren Johann Baptist Isenring mit seinem Söhnchen. Sammlung W. + T. Bosshard