Mixed bathing beach: a ‘beach of shame’

100 years ago, Weggis opened the first Strandbad, a lido or outdoor swimming area with a beach for sunbathing, with no segregation of the sexes. It gave the local tourist trade a boost, but not everyone was happy about it!

Weggis was very brave, but Weggis was very unlucky. In 1919 this resort town on Lake Lucerne built the first outdoor bathing facility in Switzerland where bathers were not segregated by sex. Given the prevailing notions of moral decency at the time, that was quite remarkable. But the grand opening planned for 13 July 1919 literally went down the drain – it poured with rain. The association Weggis Kurverein, which had built the lido without any structural arrangements to separate male and female bathers, postponed the opening for a week. And it rained again.

Woman and man at the Weggis lido around 1920. (Photo: ZHB Lucerne)

The Kurverein remained upbeat, commenting with a touch of black humour: ‘A Strandbad offers more than just light and sunshine; it also contains water.’ The impetus for the new bathing facility in Weggis, with its 90 changing cubicles, had come from the resort’s tourists: hotel owner, local mayor, major and playwright Andreas Zimmermann (1869-1943) heard that visitors considered the wooden bath houses of the lakeside hotels outdated, dark, dirty and smelly. In addition, the hard-hit tourism industry was in desperate need of a new start after World War I. This was of greater importance than the conservative values of morality and separate bathing.

It was nothing short of a nationwide sensation.

So in 1918 Zimmermann set to work persuading his colleagues in the Kurverein and local political circles, and had Lucerne architect Carl Griot build the new ‘water, fresh air and sunbathing’ facility – an open, airy and spacious complex with three wings. And most notably, no walls interfered with the view of the opposite sex.

Strandbad Weesen: more spectators than bathers. (Photo: Swiss National Museum)

This new bathing beach was given the modern name ‘lido’, and was nothing short of a nationwide sensation. Up to then, open-air bathing facilities in Switzerland had always been separated by sex, with the women on the left and the men on the right, just like in church.

But in 1919 Weggis took the leap into modernity, albeit with some very traditional elements. Mayor Zimmermann composed a piece of music called the Weggiser Strandbad-Marsch, and personally conducted its debut performance on the Weggis lakefront. The Weggis Kurverein, by contrast, took a decidedly modern approach in its advertising: posters were projected in music halls in Zurich, Bern and Basel, looking to tempt visitors even there. In fact, the Weggis bathing beach was a hot topic throughout Switzerland in cinemas, at masquerade balls and in the operetta revue Zürich, wie es weint und lacht (Zurich as it cries and laughs) at the Corso Theatre. Inspired by the uproar surrounding Weggis, the fashion boutique Grieder decorated its store windows in Zurich and Lucerne with a display of bathing costumes.

Fired up by Catholic groups, the press polemicised vigorously against the lido.

But not everyone was happy about the new style of the lido in Weggis. Fired up by Catholic groups, the press polemicised vigorously against the lido; it was even nicknamed the ‘beach of shame’ (Schandbad, a play on the German word Strandbad). Children at the Eggenbühl orphanage in nearby Hertenstein were given strict instructions to take a detour via the ‘Eichi’ on their way to school or as they walked to the village, lest they be able to catch a glimpse of the shameful goings-on at the Weggis lido.

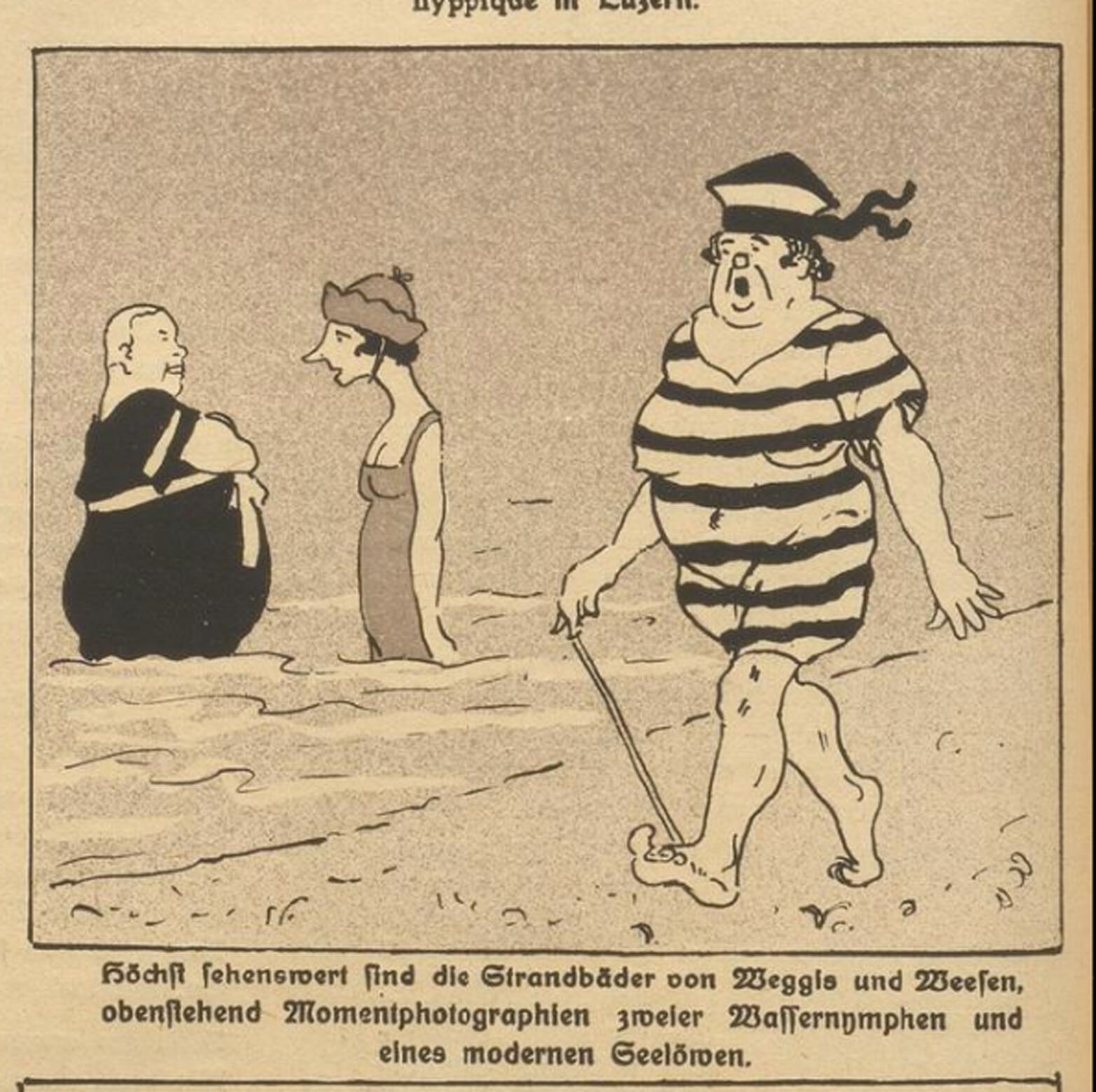

Beach life, depicted in the Swiss satirical magazine Nebelspalter, 1920. (Photo: Nebelspalter Verlag Horn)

When the complaints didn’t stop, the government of the Canton of Lucerne had to step in to sort things out. At that time (and for a long time to come) decency and propriety when bathing were hotly debated public issues, especially in Central Switzerland with its strong Catholic influence. Police officer Häfliger first checked up on what was happening at the lido in Weggis on 24 August. Despite the complaints, he had to conclude that he had noted nothing indecent: ‘Many people will take exception to the fact that both sexes are enjoying swimming and sunbathing side by side.’ But the policeman summed up matter-of-factly: ‘It’s just like any normal public swimming facility.’ So there was no need for drastic measures, and the government merely ordered that all male beachgoers over the age of 12 should wear ‘swimwear that covers the chest’, as women were required to do in any case.

The Weggis lido in 1931. (Photo: ETH Bibliothek, Image Archive)

The great influx of visitors proved Weggis right: in the first year alone, there were 31,596 visitors who, interestingly, were broken down into 18,383 bathers and 13,213 spectators – that is, gawkers. These people unashamedly photographed what remained under wraps elsewhere. The Kurverein’s annual report notes: ‘The taking of photographs in the lido became so out of hand that the bathing committee had to issue a ban. But despite the prohibition, supervisors often had cause to intervene due to illicit snapping. On the one hand, photographs would be one of the best advertisements for the establishment, but on the other hand, they can easily be misused, which could do more harm than good for the reputation of this amenity that is so beneficial to the health.’

But little scandals like this were more beneficial than damaging for the Weggis bathing beach.

One newspaper picture showing a three-year-old splashing about in Weggis caused a furore – the boy was naked. But little scandals like this were more beneficial than damaging for the Weggis bathing beach. The Weggis lido continued to be very successful. In 1927-28 the Kurverein association bought the adjacent plot of land, adding another 4,000 square metres, and enlarged the lido. 186 cubicles were now available.

Visiting bathers appreciated that: while 26,240 people came in 1927, the figure shot up to 51,575 the following year. Weggis became the model for numerous bathing establishments all over Switzerland. The public beach bathing facilities in Lucerne, Fürigen, Stansstad, Flüelen, Gersau, Vitznau (all Lake Lucerne), but also in Weesen (Lake Walen) and at Mythenquai in Zurich, are based on the example of Weggis. Weggis’s ‘beach of shame’ was a trendsetter.