A colour of distinction

The colour black hints at death, sorrow and oblivion. But black is more than just a synonym for dark times. It’s also a staple of the fashion world.

In 1949 the Parisian avant-garde Galerie Maeght on the Rue du Bac caused a scandal with the title ‘Black is a colour’. What was pure provocation in those days barely raises an eyebrow today. But until the 20th century, black – like white – wasn’t considered a ‘real’ colour. That’s what was taught at art schools.

In the early 20th century, a number of artists and fashion designers chose to make black their stylistic device. This gave black a new status, putting it on a level with red, blue, yellow and green. One of the fashion designers who made black his signature colour was Spanish couturier Cristóbal Balenciaga (1895-1972). He found an endless source of inspiration in the colour black. In 1926 Gabrielle Coco Chanel’s ‘Little Black Dress’, which first appeared on the cover of US fashion magazine Vogue that year, went down in fashion history. However, black had already been a colour of huge significance in clothing for centuries before that.

A Cristóbal Balenciaga gown from 1938. (Photo: Keystone / André Durst)

In the late 13th century, legal scholars, lawyers and magistrates in European cities began to dress in black, modelling themselves on the clergy. They believed black was virtuous and pure. From the mid-14th century, Italian financiers and businessmen wore black clothes. This allowed them to circumvent the sumptuary laws and dress codes set by the nobility, which prohibited them from wearing scarlet or the Florentine ‘peacock blue’.

A key element of courtly dress for both sexes was the white ruff.

Anna of Austria, Queen of Spain (1549-1580) painted by Alonso Sánchez Coello, 1771. (Photo: Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna)

Under the rule of Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy (1419-1467), black established itself in Burgundian court etiquette, eventually becoming the pinnacle of fashion in Europe after 1500. This was connected with Charles V, who became Emperor of Spain in 1519 and inherited the Netherlands, Spain and part of Italy. With Charles’ ascent to the throne, the Spanish court became the centre of power, and also set the tone in fashion. Together with the rigidly hierarchical etiquette of the Spanish court, what was known as Spanish court fashion developed and spread throughout Europe. It was characterised by elegance and formal austerity. The body of the courtly lady was shaped by a corset and a cone-shaped skirt. Gentlemen wore ‘Spanish breeches’, a kind of pantaloons with stockings. A key element of courtly dress for both sexes was the white ruff. Dark shades and black were preferred for precious fabrics. Nevertheless, this fashion was not solidly black. Linings were often bright and colourful, and although black had gained currency all over Europe during this period, the Spanish ideal of fashion was open to individual interpretation and often personalised, sometimes in bold colours.

Kooperation

This article originally appeared in the Landesmuseum blog. It regularly covers fascinating stories from the past. For example ‘Disinfected letters’.

The penchant for black clothing persisted until the middle of the 17th century. In many countries, including Switzerland, elements of this fashion trend survived even longer. One example of this is the Zurich church dress – one of the oldest women’s dresses in the collection of the Swiss National Museum.

The sombre woollen dress dating from the first half of the 18th century combines the fashionable black with Protestant austerity. The bodice and skirt come from the Edlibach family, one of the wealthiest and most influential families in Zurich. This dress was intended for wearing to church in the city, as shown in a 1749 work by Swiss engraver and publisher David Herrliberger (1697-1777).

Clothing should express humility and penitence.

Photograph, bridal couple in the studio, around 1865-1930, photographer unknown. (Photo: Swiss National Museum)

Throughout the entire Ancien Régime, codes of dress governed what could be worn by which social rank on what occasion. When in church, women had to wear a white bonnet, the ‘Tächli-Tüchli’. Other than for a wedding, it was the only head covering permitted in the house of worship, and as time went by it became pointed and airily high. When in mourning, a noble lady wore the white Trauerschwengel, which hung over the left shoulder.

A woman’s best dress would often be a black one.

In the eyes of the reformers, clothing was a symbol of shamefulness and sin, because it was associated with the fall of man. Clothing should express humility and penitence. The colour black did precisely that, and was considered an appropriate colour for the Protestant doctrine.

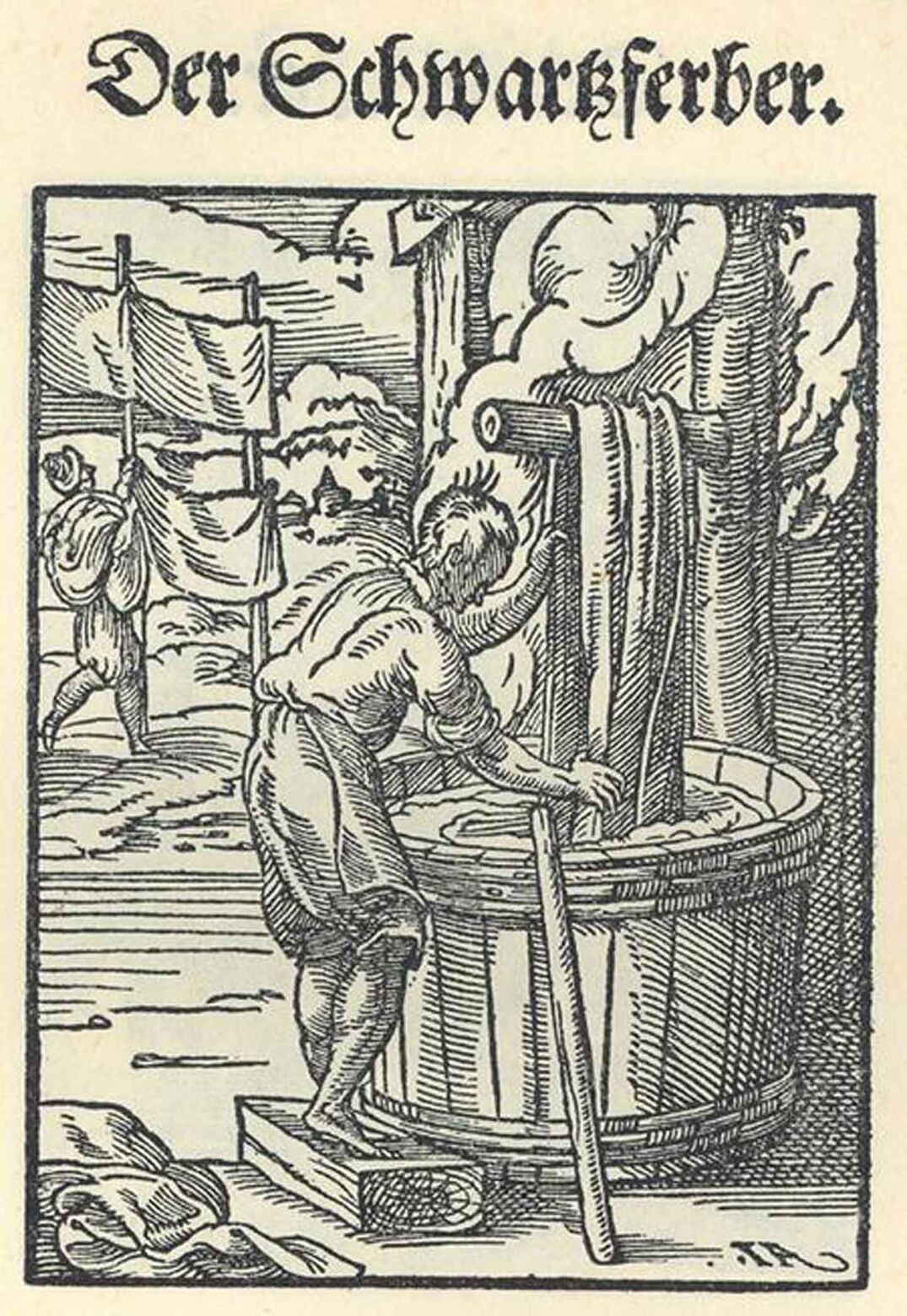

Somewhat at odds with its austere appearance, for a long time black was an expensive colour to dye. In Switzerland, this task was the responsibility of independent dyers who dyed local or imported goods on behalf of weavers and merchants.

The dyer, woodcut from Jost Amman’s Ständebuch (Book of Trades), 1568. (Photo: Swiss National Library)

Until the discovery of synthetic dyes in the mid-19th century, natural vegetable and animal pigments were used to colour fabrics. Barks, roots and fruits tended to give browns and greys. Deep black could only be obtained with oak apples, round formations on the underside of oak leaves that are caused by the eggs of gall wasps. These oak apples had to be imported from Eastern Europe, the Middle East or North Africa because they are rarely found in western oaks, or are of poor quality.

In the 16th century, there were advances in the dyer’s craft. Black textiles became more affordable, but for centuries they remained a luxury product – especially black silk. Until the late 19th century, a woman’s best dress would often be a black one. This is one of the reasons why, in the industrial age, people in Switzerland usually got married in black.

For a long time black was an expensive colour to dye.

In the 19th century, too, black was a key aspect of fashion. Black defined the gentlemanly wardrobe of elegant dandies, but also that of the population at large. The suit as we know it today was invented.

Black is currently the go-to colour for the titans of politics and business. But it is also the colour of the elegant evening attire worn on the red carpet, biker jackets, and the minimalist tailored dresses favoured by the intelligentsia. It seems black has lost none of its popularity.