Surprises and secrets: what Bahnhofstrasse offers apart from shopping

Bahnhofstrasse is one of the most famous streets in the world and is constantly changing its appearance. We’ve picked out five of its most fascinating buildings, from the unused Ballyhaus to the relocated Villa Windegg.

I was engrossed in conversation in a rooftop bar overlooking the old Ballyhaus when the German word ‘Reden’ (meaning ‘speak’) lit up in my line of sight. It was a magical moment. Those five letters on the façade of the city landmark have become an institution of Zurich life: the random generator selects a different word every day out of 700 possibilities. The idea is the brainchild of Zurich design agency WBG. They developed a new use for the protected neon balls at the request of the building’s owners.

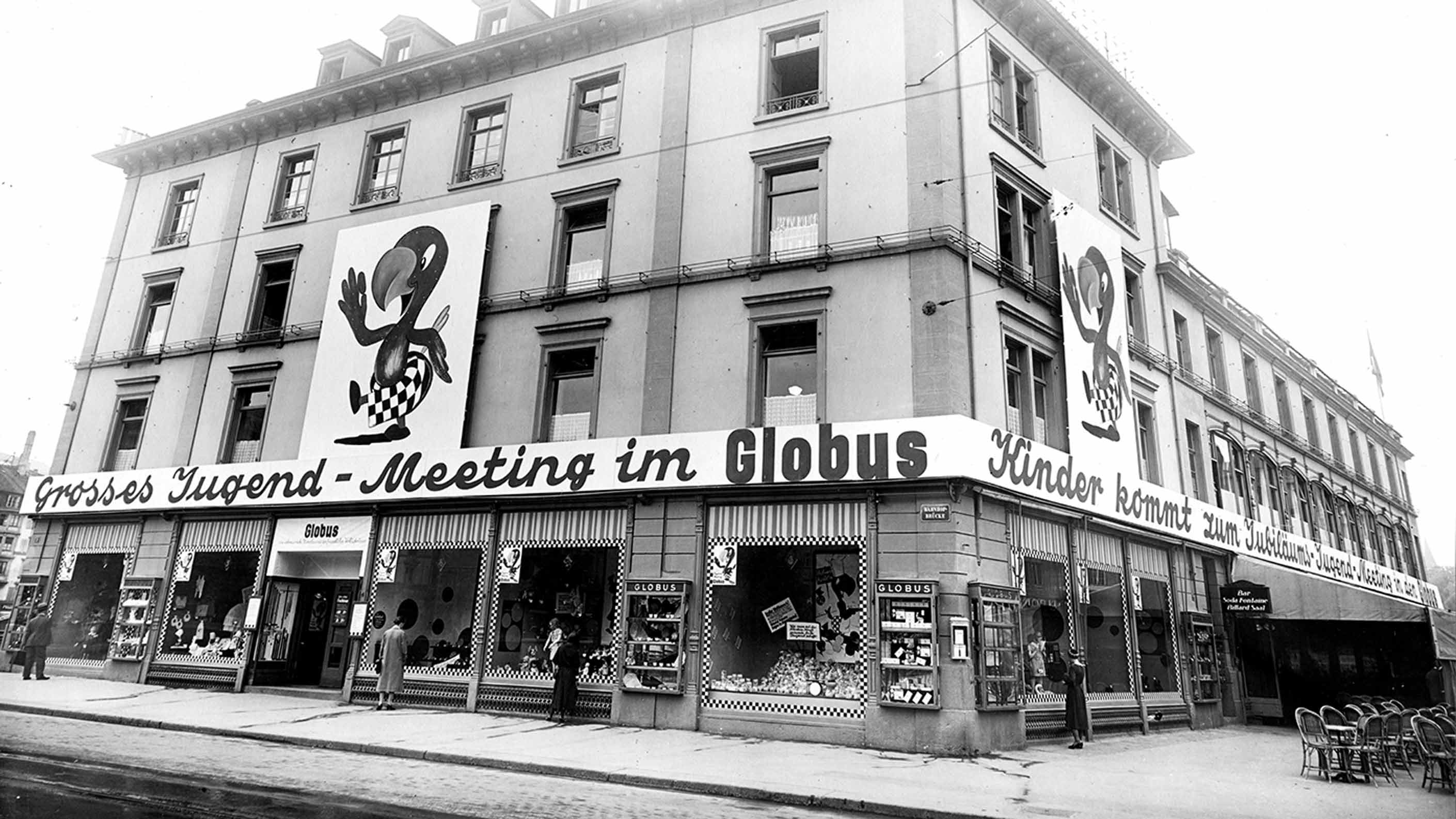

(Photo: Baugeschichtliches Archiv, Maurer Fritz)

Collecting all the words was a painstaking task for the team, as WBG partner Benedikt Flüeler recalls. ‘We spent weeks looking for words and we were constantly discussing them,’ he says.

(Photos: Designbüro WBG)

700 different words can be displayed.

They were not allowed to be offensive or political – but, rather, a subtle linguistic nudge that would elicit momentary ‘irritation with positive connotations’. ‘Chaos’ might be there, or the German words ‘Warum’ (‘why’) or ‘Zenit’ (‘zenith’).

Sometimes the word is almost too good a match. It is not always by chance. For occasions such as Christmas, the Street Parade or St Valentine’s Day, topical terms are displayed. Occasionally, the selection also responds to current events. The illuminated letters make their point at one of the most prominent locations at the tight junction of Bahnhofstrasse and Rennweg. It is not just the neon balls that are protected, but also the building itself, dating from 1968, with its rib-like façade. It was designed by the architecture firm Haefeli Moser Steiger, which is regarded as a pioneer of the modern style.

Sinners used to be put on public display here.

(Photo: Baugeschichtliches Archiv, Gloor Gottfried)

There is a complete contrast to this immediately opposite, at Bahnhofstrasse 69 and 69a. The ‘Haus zur Trülle’ from 1897 stands out thanks to its bay windows, balconies, mansards, art nouveau ornaments and a striking spire. The three storeys above the three shopping floors were originally grand apartments – hence the balconies.

(Photo: Wikipedia)

From the 1950s, the property was home to the prestigious household-goods business Séquin-Dormann, well known all over the city, which closed down in 2004. The name ‘Trülle’ harks back to something less prestigious in nature. Originally, in the Middle Ages, this spot was the location of a cage – or ‘Trülle’ – rotating on its axis, in which ‘poor sinners’ were put on public display. That scene is represented on the relief at the top of the tympanum, which was removed in the 1950s but reconstructed during the restoration in 2005.

(Photo: Baugeschichtliches Archiv, Wolf-Bender's Erben)

A little higher up in the direction of the lake, almost at Paradeplatz, there is one more protected building. Peterhof at Bahnhofstrasse 33, also known as the Grieder-Haus, impresses onlookers with its stepped gable at a height of 32 metres. At street level, the building is supported by striking pillars. If you let your eye follow the pillars upwards, you will discover figures carved from shell limestone on the third floor. These are guild masters and other historical figures from Zurich – all male, of course.

(Photo: Wikipedia)

Villa Windegg, which used to stand here, is no longer to be seen. In 1913, something amazing happened: the villa was dismantled, brick by brick, and re-erected more than one kilometre away at Bellerivestrasse 10, by the Utoquai baths, where it stands to this day. Villa Windegg had been one of the very first buildings on Zurich’s Bahnhofstrasse.

This villa is no longer on Bahnhofstrasse.

(Photo: Baugeschichtliches Archiv)

The most famous street in Zurich is not actually very old at all. As recently as the early 19th century this was the location of the Fröschengraben moat, which was part of the city’s fortifications and lay outside the city wall. In 1864, this water channel was filled in, and the present middle section of Bahnhofstrasse was built in its place. The entrance to the neat Augustinergasse with its colourful bay-windowed houses was formerly the location of the Augustinerbollwerk, a circular tower with a gate, which formed part of the long-destroyed city wall.

(Photo: Wikipedia)

Today, the building at Bahnhofstrasse 48 stands here. Look up, and you will see a fine, domed tower, adorned across two storeys by two columns. This edifice, erected in 1874, is made of sandstone, like many of the buildings here. At the level of the passers-by, the corner tower has constantly undergone radical reconstruction. In 1910, when Bahnhofstrasse was starting to turn more and more into a shopping boulevard, the walls were opened up and display windows were inserted. This was followed in 1960 by the construction of a narrow canopy over the display windows. Then, during the renovation in 1990 by Tilla Theus und Partner, two massive new columns were erected, also made from solid sandstone.

(Photo: Baugeschichtliches Archiv)

(Photo: Wikipedia)

You will also be struck by an impressive corner tower at the very entrance to Bahnhofstrasse 91/93. This is the present-day Hotel Schweizerhof, one of the older buildings on Bahnhofstrasse, which was built immediately opposite the central train station in 1877 as the Hotel National. That hotel had a Moorish hall, inspired by the Alhambra in Granada. In 1886 it welcomed the pope and Bismarck as guests, and in 1908 it was given an art nouveau façade, which – like the whole building – has had protected status since 1978. At the very top of the corner tower, the bustle and traffic around Bahnhofplatz have been watched over for 144 years by four caryatids, female figures carved from stone. These women standing like columns would probably have a few tales to tell, if only they could speak.

Book recommendation

Werner Huber: Bahnhofstrasse Zürich (Published in German by Hochparterre AG)